This month, you’ll find a piece I’ve written in Vintage Script, a new magazine dedicated to all things vintage, historical and retro. What’s most delightful about it is the range of different historical periods, as well as the different approaches taken to bringing them to life. In this month’s edition you’ll find stories on the history of tea time, flapper girls of the 1920s, Durham Cathedral and the truth behind the Scarlet Pimpernel. It really is well worth a read, so do please visit the web site and take a look.

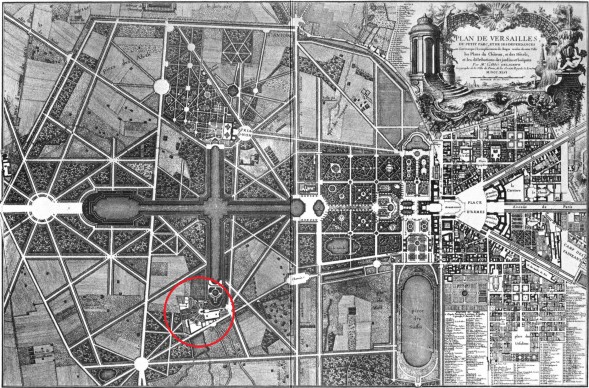

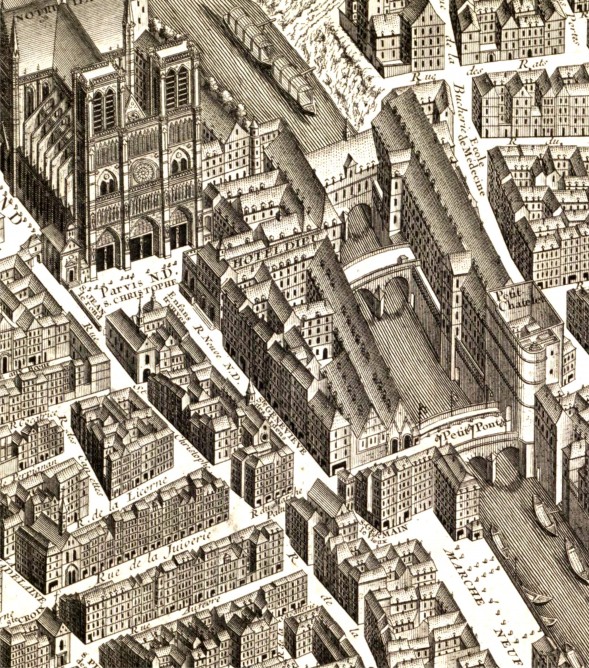

The Versailles Menagerie during Louis XIV’s reign, by D’Aveline.

In an attempt to whet your appetite, here’s an extract from my article on the history of the Royal Menagerie at Versailles. You’ll have to take my word for it, but the stuff I’ve cut out here is stupendous, so you really should get the magazine!

We take up the story from Louis XIV’s death. Before the Sun King, the French Royals had not had a permanent menagerie but instead contented themselves with a band of exotic or entertaining animals which followed them around their various royal residences. Louis XIV established two permanent menageries – one at Vincennes and one at Versailles, each with a different purpose and personality. The Vincennes menagerie was used for dramatic fights, such as the battle between a tiger and an elephant staged to amuse the Persian ambassador in 1682. The Versailles menagerie, on the other hand, was a model of order and rationality, where the far more fortunate animals were intended for peaceful display and, as all things at the palace, to augment the glory and prestige of the king. The conflict between these two very different styles of menagerie reflected the conflicts in Louis’ personality and style of leadership, but by the end of his reign the Versailles style had clearly won out, and the Vincennes zoo was closed.

Map of Versailles, by Delagrive (1689-1757), 1746 (via Wikimedia Commons), with the location of the menagerie highlighted. Below, the former site of the menagerie today, from Google Maps.

[cetsEmbedGmap src=http://maps.google.co.uk/maps?q=versailles&hl=en&ll=48.804772,2.09502&spn=0.013143,0.033023&t=h&z=16 width=598 height=400 marginwidth=0 marginheight=0 frameborder=0 scrolling=no]

In some magical way Versailles transformed itself to match the character of the king at its heart, so when the Sun King died and was succeeded by his grandson Louis XV, everything changed. Louis XV was more interested in hunting animals than observing them in his menagerie, and his taste for exotic wildlife restricted itself more or less to Madame de Pompadour and his seraglio of royal mistresses. Animal gifts kept coming from every corner of the ever-expanding French trading empire, but the king lacked both the funds and the inclination to give them much of a welcome. When an elephant arrived in 1772, it was forced to walk more than three hundred miles from the coast to Versailles.

One can imagine the elephant was quite miffed about the debacle (but must have created quite a stir in the towns and villages along the road) and things got no better once it arrived at Versailles. The pond dug for the exotic birds to wade in was full of silt. The wall enclosing the rhinoceros which arrived two years earlier was literally crumbling (not a good thing, as the rhino was no doubt angered by visitors who laughed at its absurdly wrinkled skin). Even the animals in the once beautiful paintings which lined the walls of the observation room were faded and peeling. The elephant stuck it out for as long as possible, but in 1782, broke free of its enclosure and rampaged round the grounds of Versailles. Next morning, a strange new elephant-shaped island was found floating in the Grand Canal.

Sadly, the elephant died too late to witness the last gasp of the royal menagerie. Louis XVI had ascended the throne in 1775, and found a financial and political situation as neglected as the menagerie. Unlike his grandfather Louis XV, Louis XVI could not rely on winning charm to see him through – he had none. He was therefore much more attuned to symbolism, and strove constantly, in the face of an ever-deepening crisis, to project an image of undimmed power and royal prestige.

Although they never knew it, the animals of the menagerie were a perfect instrument for this. The very fact that they were there at all spoke eloquently of the scope and scale of the king’s influence. Overcoming the difficulties of finding and catching such rare and beautiful creatures, overcoming the problems of long distance travel and communication, overcoming the self-interest of every captain and sailor along the way who might have sold his precious cargo, the king had commanded that animals be brought, and they had come. The strength of his will even seemed to overcome death itself: such animals were notoriously difficult to keep alive on long voyages. Exotic birds especially had an irksome habit of dropping down dead when cannon fired, or simply pining away. Whispers began to circulate that the most beautiful birds of all simply could not live without their liberty.

Louis sent out a shopping list to his representatives around the world. “An elephant; 2 zebras, male and female; mandrill and baboon monkeys; 6 guineafoul”. Perhaps Louis wished to tame the zebras and teach them to draw his carriage, as some of his more flamboyant contemporaries did. But Louis was never to receive an elephant and only got one of the zebras he asked for, though the menagerie did benefit from an influx of new inmates, including a lion, a panther, some hyenas, a tiger, some ostriches and several kinds of monkey.

The popularity of the menagerie was also boosted by great vogue for the study of nature that flowered during Louis XVI’s reign. Naturalists had grown tired of studying the dusty tombs of Cabinets of Curiosity, where brown pickled fish bobbed in vinegar and faded birds stood stuffed in a peculiar imitation of life that seemed to startle the thought of death into everyone who looked at them. There was now, prompted by the bestselling work of Buffon, a desire to observe living animals. Now then, the animals of the menagerie had a new torment, as fashionable men and women toured the menagerie, staring deep into the eyes of monkeys and, with a pained expression, wondered aloud “What is it to be human?”. Nobody ever seemed to wonder what it is to be monkey.

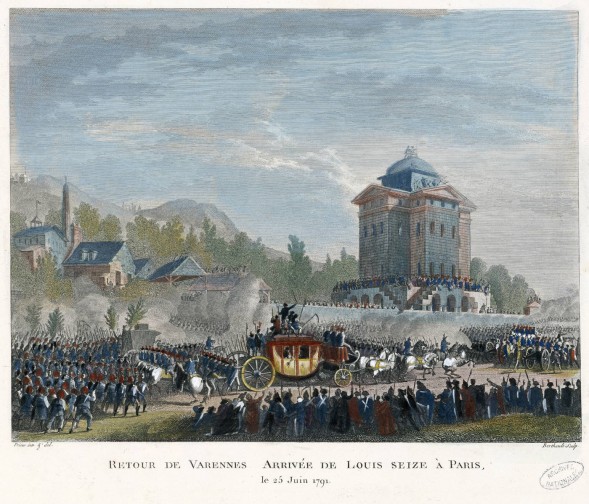

As it turned out, of course, even if Louis had managed to obtain a hundred zebras to draw his carriage, they couldn’t have saved him from the coming of the Revolution. Perhaps the animals noticed a glow of torchlight up at the palace on the night in October 1789 when a crowd of thousands arrived to remove the royal family and take them back to Paris (henceforth to be caged and regarded with the same mixture of awed and disgusted curiosity that the inhabitants of the menagerie had been).

The menagerie must have been a sad and dispiritingly quiet place for the next couple of years, as history was written elsewhere, and the fate of a dwindling bunch of pampered pets was of no importance. But, in a perverse way, the violence and inhumanity of the revolution was to foster a new concern for these animals. After a few years, with the Terror in full flow, the bourgeois leaders of the Revolution began to grow concerned that the populace was becoming too accustomed to blood, too wild. They needed to be brought back to the civilising influence of orderly society – and what better way to demonstrate its advantages than through the example of these wild animals. If even a lion, when it is well cared for by enlightened rulers, can be tamed and made gentle, then there’s hope for anyone. This attitude to animals was extraordinary: in 1794, the Paris Commune received complaints about ‘disgusting displays’ of animals in the Place de la Révolution, but none about the twenty guillotinings that took place in the same square every day.

At the last minute, the few remaining animals of the royal menagerie, which had been due to be killed and stuffed, were saved, and made a part of plans for a new state menagerie at the Jardin des Plantes in Paris. Following a ban on animal shows, the authorities had sent out agents to round up all wild animals being kept or sold in Paris for this purpose. The only problem was, there was nowhere to put them except the basement of the museum at the Jardins des Plantes.

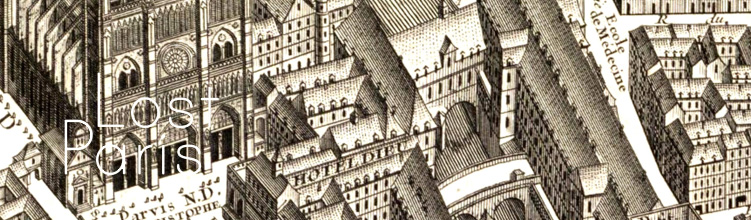

The wrinkly rhinoceros died before it could make the journey (run through, according to legend, by a revolutionary’s sabre), but the lion from Versailles was taken to Paris in 1794, and found itself in a room full of the motliest collection of animals since the Ark. Here was a leopard, there a sea lion. Perched on a crate were three eagles, bleating in the corner were three sheep with various lurid deformities, and god-knows-where was what had been promised to be a sea lion when the harassed zookeeper agreed to take it on, but was discovered on arrival to be a polar bear. There were in total 32 mammals and 26 birds.

Gradually a permanent, if very basic, home for these forlorn creatures was put together, and, amid trumpeting revolutionary rhetoric that the animals would “no longer wear on their brows, as in the menageries built by the pomp of kings, the brand of slavery”, its doors were opened to the public. This new, state menagerie was intended to be a pacifying haven of contemplation and rational study. It didn’t quite work out that way. As soon as the doors opened, the citizens of Paris made a beeline for the old lion from Versailles. They pulled at his fur, and shouted abuse when he tried to sleep, and spat at him because, they said, he used to be a king too.

The lion bore his torment for a short while, but in the famine-frosted winter of 1795, when there was no money for food and none to buy anyway, half the animals died, the lion probably among them. After this time, conditions at the menagerie slowly improved, and with the conquests of Napoleon, it was repopulated with inhabitants from new outposts of empire.

Today, there’s no trace of the menagerie beneath the impeccably manicured lawns of Versailles, but a piece of it survives. If you go to the Jardins des Plantes, past the small zoo which still survives and into the Natural History Museum, you’ll find a large glass case, containing a leathery rhinoceros, the first to ever be stuffed and preserved. Today people file by and study him quietly, as civilised and dispassionate as they were always meant to be, save perhaps for the occasional chuckle at his absurdly wrinkly skin. But this is an extraordinary survivor, called across the sea by the last pulse of royal power from France, witness to the end of an era, one of the last beings ever to truly live at Versailles, victim of the violence of the revolution – and yet, here he is. Through all the storms of history and politics, the revolutions and counter-revolutions, monarchies and republics, wars and peaces, the rhinoceros has stood safe in its glass case. Even today, the Versailles menagerie is drawing long-severed worlds into strange meetings.

Louis XV’s rhinoceros, at the Natural History Museum in Paris.

The rhinoceros was recently featured in an exhibition at Versailles, ‘Sciences and Curiosities at the Court of Versailles, which I’m bereft at having missed. This nice little video was made to coincide with the exhibition.

More

- ‘Elephant Slaves and Pampered Parrots: Exotic Animals in Eighteenth-Century Paris’ (2002) by Louise E. Robbins has lots more fascinating detail on the menagerie, and 18th century Parisians’ relationship with animals.