On the morning of 11th August 1792, an exhausted and increasingly sweaty royal family sat in the reporters’ box of the National Assembly, a stone’s throw from the Seine in Paris. The night before, the Tuileries (the 16th-century royal palace near the Louvre which had been their residence since they were removed from Versailles in 1789) had been invaded by the people, and a chaotic and brutal battled ensued. The king had been forced to flee the palace and seek refuge with the Assembly.

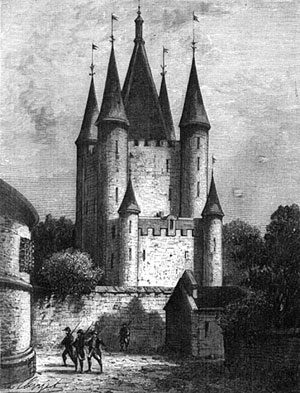

As debate raged around them over the future of the monarchy, one thing was already clear. The Tuileries was no longer a suitable residence for the royal family, and an alternative must be found urgently. And so it was that on 13th August, Louis, Marie Antoinette and their children were transported to the Temple. This would have come as no great surprise to Marie Antoinette, indeed she had predicted that they would ultimately be moved there several months before it came to pass. But it was nonetheless a frightening development. Marie Antoinette had always disliked the Temple – a complex of buildings including a rather lovely seventeenth-century palace and the far more ominous Tower, a decaying hulk of a building constructed by the Knights Templar in the 12th century. Earlier in her life, Marie Antoinette was even said to have suggested to her brother-in-law (then owner of the palace) that the Tower should be knocked down.

The prospect of life in the Temple was very different to the one they had known in the Tuileries. Though certainly well past its best, and a precipitous step down from Versailles, the Tuileries was at least a royal palace, and while they had been tucked away there, a sort of calm had descended, allowing questions over the exact status of the royal family to be conveniently postponed or half-answered. The family had enjoyed considerable independence in the Tuileries, where there was space to walk outside and to house supporters, and enough leeway for many of the traditions and rites of Versailles to continue in some form or another. Security had even been lax enough to allow the royal party to make its ill-fated escape attempt earlier in the year.

The Temple, it was clear to everyone, was to allow none of this ambiguity. In moving to the Temple, Marie Antoinette and her family were being imprisoned, physically and psychologically. Though their quarters were cramped, damp and cold, there were still touches of luxury in their furnishings, meals continued to be lavish, and the King was allowed his own study. What made the real difference was that the King and Queen were now strictly monitored and controlled by jailers who openly disrespected them, and clearly enjoyed inflicting what Antonia Fraser calls ‘petty humilations’ on them whenever possible. What’s more, any chance of escape, except in the most fervid daydreams of die-hard monarchists and paranoid republicans, had now well and truly passed. Most painful of all for the king and queen must have been the dawning realisation that they were now powerless – locked out of the way whilst their fate, and that of France, was being decided elsewhere.

From now on, events moved rapidly. On 21st September, the National Assembly declared France a republic, and abolished the monarchy – adding new urgency to the question of what should be done with its former monarchs. In October, Louis was separated from his family in preparation for trial. His jailers presented him with a choice – he could be allowed to see his children during this time, or they could be left with Marie Antoinette, but it must be one or the other. They would not be allowed to see both parents. Louis chose to leave the children with their mother, and he would be reunited with his family just one more time, on the night before his execution on 21st January 1793. He bade them a tearful farewell, but promised to see them again the next morning before he was taken away.

Louis was fascinated by history, and had spent much of his life reading history books. Some observers had wondered why, because the king had never seemed to learn much from it. But recently he had been fixated on the story of Charles I of England, and in particular the fearless and noble way he met his own execution. It was said that Charles had secretly worn two overshirts as he stepped onto the scaffold that January morning, so that his people would not see him shiver from cold and think him afraid. Louis was determined that his people should not see him shiver, finding, as he faced his death, a resolution and strength he had so often lacked in life.

This newfound resilience called upon all of Louis’ emotional reserves, so when dawn came, he found himself unable to face the strain of of seeing his family again. He broke his promise. Marie Antoinette and her children waited in the Tower, unaware of what was going on. It was only when they heard drums and a huge cheer echoing round the streets that they knew Louis was dead. Later, some would claim that in that instant Marie Antoinette turned to her son Louis-Charles and said ‘The king is dead, long live the king’, expressing the tradition that monarchy itself never dies – kings come and go, but kingship passes down a divinely-ordained and unbroken ancient line.

The comment seems emotionally out of place, but whether or not Marie Antoinette actually said it, it was true that, with French law forbidding a woman to hold the crown, for those unwilling to accept that monarchy in France was a thing of the past, the seven-year-old Louis Charles had suddenly become King Louis XVII.

Louis Charles can’t have remembered much of life before the revolution, and in one way or another conflict had overshadowed his whole life. Portraits of the boy show an angelic and spirited but delicate looking child, and this matches well with the reports of everyone who knew him. He was said to be loyal and loving, and his stubborn pride was certainly forgiveable (indeed, almost a requirement) in a dauphin of France. He was adored by his parents and his sisters, and proved capable of charming even his most implacable enemies. The revolution would severely test the boy, and though he endured numerous terrifying episodes in which he and his family could easily have been killed, he did not emerge unscathed. These experiences seem in particular to have reinforced a pair of key character traits which Marie Antoinette and others had noted despairingly even before the upheavals of 1789. Firstly, Louis Charles had always been easily scared. At Versailles, more often than not it was the sound of dogs that startled him, but by 1793 his nerves had become so frayed that he cowered at almost any disturbance. Secondly, Louis Charles, like many young boys, had a tendency to repeat things that he had heard too freely, adding his own invented details to enhance the telling, without consciously meaning to lie. This it seems was a symptom of a more general desire to please, and to be loved.

This particular combination of character traits, though not exactly unusual in a boy of his age, was to prove disastrous in the new phase of Louis Charles’ life that was now beginning. With his father dead and mistrust and hatred for Marie Antoinette as widespread as ever, it was decided that the boy should be separated from his mother. This was done in June, without warning. When men entered to take him away, Marie Antoinette clung to her son for over an hour, refusing to release him even when her life was threatened. Only when the guards shifted tactic and threatened her daughter did Marie Antoinette finally relent.

Louis Charles now posed a problem for the revolutionary authorities. He was too young to be tried like his father, and he could certainly not be allowed to go into exile, where he would provide the counter-revolutionaries with a potent figurehead. And though the problem of his father had been solved by killing him, doing the same to this cherubic, innocent boy would present a most unpleasant image of the revolution to the world, and could inspire a backlash of monarchist sympathy. So, it seems to have been decided, the only thing to do with Louis Charles was to keep him out of sight of the public and hope that in time he would be forgotten. More deliciously for some, a close, solitary imprisonment even presented the tantalising possibility that Louis Charles might be made to forget himself. The Commune, which oversaw the imprisonment of Louis Charles, spoke explicitly in terms of a ‘re-education’, and the ultimate hope was that the boy should ‘lose the recollection of his royalty’, in the words of Jacques-René Hébert, and become a revolutionary.

The man chosen for this ‘re-education’ would be, in any other circumstances, an unlikely tutor. Antoine Simon was one of life’s failures, making a mess of everything he tried his hand at. Training initially as a shoemaker, nobody was interested in buying his wares, and his cheap tavern by the Seine proved equally disastrous. His luck seemed in when his first wife died and by some miracle he managed to attract another who came with a hefty dowry attached, but this too was soon frittered away. Rather than accepting that his own laziness and lack of business acumen had been the primary cause of the string of failures that riddled his adult life, Simon became increasingly angry and bitter, blaming anyone but himself for keeping him from the success he richly deserved. The Revolution was a gift to Simon, dovetailing nicely with his paranoid conspiracy theories, encouraging him to paint the aristocracy as being responsible for keeping men like him in their lowly stations. Even in the midst of this revolution, dominated by legendary characters and awesome personalities, Simon’s commitment and zeal marked him out, and he was soon noticed by those in authority. Simon was a man who would put the revolution above anything, and would not allow sentiment or affection to prevent him from following orders. Consequently when Jacques-René Hébert and his superiors at the Commune were searching for a man to watch over Louis Charles and break his royal spirit, Simon was a natural choice. One can only imagine Simon’s feelings on discovering his new destiny. He had spent his life railing impotently against the aristocratic Hydra laying waste to his hopes and dreams. Now one of its last remaining heads was his to control – and destroy.

Louis Charles’ re-education could not begin immediately as for the first few days he simply huddled in a corner, weeping uncontrollably, terrified by the slightest noise. Eventually though, things began to settle into a routine, and at least in this early stage, Louis Charles was not treated too badly. He was washed and his clothes were cleaned, he was given toys and sometimes even got to play with the laundry woman’s daughter. He was allowed outside into a small garden for air, and on one of these occasions Louis Charles found the courage to demand of some officials who had come to see him ‘I want to know what law you are using that says I should be separated from my mother… Show me this law, I want to see it!. Louis Charles’ short walk to the garden took him directly past Marie Antoinette’s cell, and if she craned her neck to a certain crack in the wall she could catch the merest glimpse of him as he walked by. Marie Thérèse wrote later that her mother would stand for hours with her eye crammed against that crack, waiting to see her son – ‘it was her sole hope, her sole occupation’.

In these early days of his isolation, there seems to have been some uncertainty about what exactly was to be done with Louis Charles. Simon didn’t like uncertainty, and resolved to clarify the situation. In July he went to the Commune, demanding what their intentions were for the boy. Their answer was clear and unequivocal – ‘We want to get rid of him!’.

From this point on the life of Louis Charles took a far more sinister turn.