The most striking thing about reading the record of Marie Antoinette’s trial before the Revolutionary Tribunal in October 1793 is realising what an astonishing mess the whole thing really was. In most other accounts, revolutionary justice always seems so swift, so merciless, so ruthlessly efficient. Many of those who stood trial before the Tribunal had few real crimes to answer for, and yet they were quickly exposed as monsters and condemned to die by public guillotining. So, on the balance of things, you would have thought Marie Antoinette – a figure universally despised by a populace which had been spoonfed wild propaganda and grotesque fantasies about her since before she even came to France – wouldn’t have presented many problems.

And yet as you keep reading the account of her two day trial, one question increasingly plays on your mind – is this it?

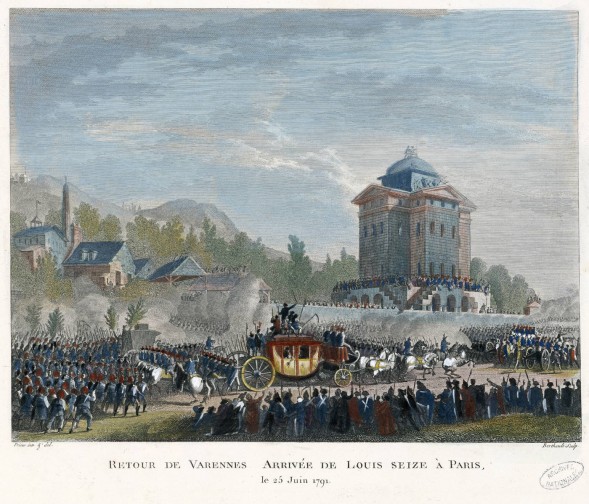

The king’s trial and execution had turned out to be a painful and awkward affair. Louis argued his case with a quiet dignity, and the final vote to decide his fate revealed the extent of lingering doubt and latent sympathy for the former king. 361 deputies voted for Louis’ immediate execution, but 288 voted against the death penalty. On the streets of Paris, where public executions had become something of a spectator sport, Louis’ end brought its share of rejoicing, but somehow failed to offer the hoped-for catharsis, the line in the sand between the old regime and the revolutionary future.

If Louis’ execution had the atmosphere of a funeral, Marie Antoinette’s was expected to have more in common with a rowdy wake. The people had never hated Louis as much as they had come to despise Marie Antoinette, indeed in the popular version of events Louis was usually cast as a hapless, blundering but essentially good puppet being manipulated by the calculating Marie Antoinette for her own nefarious ends. Until she was removed from the equation, the revolution could never feel entirely secure.

The trial was presided over by Antoine Quentin Fouquier-Tinville, President of the Tribunal. He oversaw all the key trials of the period, and had earned a reputation as one of the revolution’s most fearsome figures. Ruthless and single-minded in the pursuit of revolutionary justice, rumour had it that he was terrified of the people, sleeping with an armed guard at his door and a hatchet under his pillow. One can only imagine his feelings as he received word that Marie Antoinette was finally to stand before his court. Here was an opportunity for a spectacular showpiece, a chance to reaffirm and reenergise the revolution. All that was really necessary was to provide a reminder of the crimes that the majority of people were already convinced Marie Antoinette had committed.

Marie Antoinette was given just two days to prepare for her trial, unlike her husband who had been afforded months tucked away with his lawyers at the Temple. As per the rules of the Tribunal, her lawyers would not be allowed to speak for her during the trial itself, so she alone must respond to all examination.

On 14th October, when the galleries had filled with expectant crowds (including the diehard groups of women who attended so many trials and executions that they now brought their knitting with them to do while they watched), the trial commenced. As expected Foquier-Tinville began with a lengthy, vitriolic speech in which he outlined the charges, and placed Marie Antoinette in a long line of infamously wicked women ‘like Messalina, Brunhilda, Fredegund and Medici’. He described her as ‘the scourge and the blood-sucker of the French’, and in language reminiscent of witchcraft accusations talked of the ‘creatures’ and ‘midnight meetings’ she employed.

From the outset then it was clear that the trial was to proceed along familiar lines of character assassination, the rationale seemingly being that proving Marie Antoinette’s complete moral degeneracy would show her capable of committing any crime, thereby absolving the need to prove her guilty of actually committing particular ones. Anyone with a bad word to say about Marie Antoinette, however unilluminating, is roped in to the court. Thus, Jean Baptiste Lapiere, a former guard at the Tuileries, testifies that he was on duty on the night the royal family made their escape, ‘but not withstanding his vigilence he had seen nothing’. Pierre Joseph Terrason observes that when the family had been captured and returned to the Tuileries, he saw Marie Antoinette “throw upon the national guards who escorted her, and likewise upon the citizens in her way as she passed along, a most vindictive glance; which suggested to me the idea that she would certainly take revenge; in reality a short time after the scene of [the massacre at] the Champ de Mars took place”. Rene Mallet, a former maid at Versailles, even goes so far as to relay a rumour she had heard that Marie Antoinette had conceived a plot to assassinate the Duke of Orleans, keeping two pistols secreted in her skirts in case any opportunity to carry out the murderous plan should present itself.

Evidence like this dominates the trial in part because of the corner the revolutionary authorities had backed themselves into. Most of the people who ever had any real contact with Marie Antoinette had long since fled France, or had already faced the Tribunal themselves. A few such associates were found for the trial, but Fouqier-Tinville is so keen to establish that they too are guilty and odious that he is forced to demolish their credibility and render their testimony next to useless. Jean-Frederic Latour Dupin gave evidence on the second day of the trial. As an ex-Minister of War he initially claims to know nothing of any of the charges laid against Marie Antoinette, and rather than pressing him on this, Fouqier-Tinville devotes much time to scrutinising Latour Dupin’s actions as minister, many of which have little or no bearing on Marie Antoinette. Even when he eventually does prompt Latour Dupin to concede that Marie Antoinette had asked him for military details, which he duly supplied, Fouqier-Tinville quickly becomes distracted by questions over whether she ‘abused the influence you had over your husband, in asking him continually for drafts on the public treasury?’. The crucial point of whether or not Marie Antoinette betrayed the armies of France (so pivotal to the charge of treason at the centre of the trial) is therefore never satisfactorily resolved.

The trial often falls into a pattern, with Fouqier-Tinville throwing accusations at Marie Antoinette without any tangible evidence, and Marie Antoinette sticking to what must have been her planned approach of giving short, unemotional responses – usually one word answers, or simply stating that she had no knowledge of what witnesses alleged.

Given the motley crew of witnesses assembled for the trial and the paltry store of evidence, the revolutionary authorities must have known that it had the makings of a repeat of Louis’ confused and messy hearing. What they needed was a piece of killer evidence – some new juicy scandal that even the rumour-weary people of Paris had never heard before – to turn this trial and execution into the triumph they needed it to be. And in searching for someone to take on the role of showman/muck-racker, they didn’t have to look very far.

Jacques René Hébert was one of those deliciously intriguing personalities that make studying the French Revolution such a joy. As editor of the incendiary (and, even today, shockingly foul-mouthed) newspaper Le Père Duchesne, Hébert had achieved great influence among his hundreds of thousands of readers, and had already made repeated calls for the destruction of Marie Antoinette, ‘the Austrian bitch’. Hébert himself was a figure riddled with contradictions. His newspaper was peppered with obscene language and visceral, violent imagery, and he adopted the persona of the archetypal sans-culotte; yet he himself came from a bourgeois background, dressed finely and, in some accounts, was in private a remarkably ordinary family man. And while his huge popular following made him the envy (and, latterly, the enemy) of figures as powerful as Robespierre, Hebert was never able to win a major elected position, and his attempts to do so ended in frankly embarrassing results.

He was, however, able to secure a position as the second substitute of the procureur of the Paris commune, and in this position he shared responsibility for the imprisonment of the royal family in the Temple. In this capacity he was privy to every detail of the actions of the family, shared responsibility for the decision to separate Louis Charles from his mother (as examined in a previous story) and from then enjoyed a powerful influence over the boy. For a man like Hébert this was a golden opportunity. All he had to do now was figure out how to use it.

Marie Antoinette’s personality had been assailed on almost every front – her wild extravagance was well known and unquestioned; her supposedly perverse and numberless sexual proclivities had been the stock in trade of pornographers and gossips for years; and at one and the same time she was dismissed as intellectually vapid and reviled as a cunning, Machiavellian enemy of the revolution. But through all this, one positive light had continued to shine on Marie Antoinette: the glow of motherhood. This aspect of her role was especially important to Marie Antoinette herself; in part because it had taken her so agonisingly long to become pregnant, in part, perhaps, because of the epic example of motherhood provided by her mother the Empress Maria Theresa, and in part simply because of her own naturally maternal personality. The image had been deliberately fostered through public events and in official portraits, especially those of preferred painter Élisabeth-Louise Vigée-Le Brun. That it had a profound impact on the public was powerfully demonstrated in October 1789 when the crowds who invaded Versailles called for Marie Antoinette to appear before them on a balcony. When she attempted to come out with her family, the mob yelled ‘No children! No children!’, as if wanting to strip her of the cushioning aura of her motherhood.

If there was one thing Hébert knew it was how to whip up the people, and so he quickly arrived at a plan to destroy the one last vestige of humanity left in the public image of Marie Antoinette, and speed her on her way to the guillotine. At some point, it was mentioned to Hébert that when Louis Charles was frightened Marie Antoinette would comfort him and let him sleep in her bed. This planted the seeds of an idea. Hébert decided to frame a story that Marie Antoinette abused her son sexually, teaching him to masturbate and making him sexually dependant upon her. There has been some speculation that in order to provide this story with a foundation, Hébert ordered Louis Charles’ guard Simon to encourage him to masturbate, and even bring prostitutes into his cell. Certainly, Louis Charles was subject to all manner of physical abuse by his jailers, and there is no way of knowing how far this extended. However, it is clear that Hébert knew better than most men that truth was far less important than what people could be made to believe. He operated in the realm of words rather than action, and would have seen that subjecting the boy to actual sexual abuse was unnecessary for the plan to succeed. Louis Charles was, anyway, a vulnerable and easily-led boy.

In early October 1793 Hébert visited Louis Charles in the Tuileries, and got him to sign a pre-drafted confession. Most cruelly, Louis Charles was also made to confront his sister and aunt (who had not seen him for 3 months) with the accusations, and they too were then interrogated. Though only 15 years old and unable to understand the full weight of the accusation, Marie-Thérèse knew enough to recognise it as an obscene lie, and was profoundly upset by the incident. Aunt Elisabeth refused even to respond to the questions.

Armed with this coup de grâce, Hebert arrived at the great hall of the Revolutionary Tribunal on 14th October for Marie Antoinette’s trial. When called to give evidence, he began unremarkably enough, with recollections of finding counter-revolutionary symbols belonging to Marie Antoinette, and insinuations about Lafayette’s role in the escape plan. Is it too much to detect a little nervousness in Hébert’s opening remarks? He’s certainly watching his language, and there’s something hesitant, stumbly in his hotchpotch accusations. Finally though, he gets to the point, and the wind floods back into his sails.

In fine, young Capet, whose constitution became every day impaired, was surprised by Simon in practices destructive to his health, and at his period of life very uncommon; he was asked who had instructed him in these practices; he replied that it was his mother and his aunt.

Hebert went on, keen to prove that Marie Antoinette could not even engage in child abuse without some still more sinister motive.

There is reason to believe that this criminal indulgence was not dictated by the love of pleasure, but by the political hope of enervating the constitution of the child, whom they supposed destined to sit on the throne, in order that they might acquire ascendancy over his mind.

The court fell silent as the accusations landed, then an ambiguous murmur rippled round the crowd. Fouquier-Tinville hastily asked Marie Antoinette what she had to respond, Marie Antoinette replied “I have no knowledge of the facts of which Hebert speaks”. Even Fouquier-Tinville now seems unwilling to delve any deeper into this appalling line of questioning, and instead begins asking questions about some of Hébert’s earlier, more mundane accusations. He is interrupted by a member of the jury, who demands that the Queen answer the accusations about her son.

Suddenly the bricked-off, emotionless, almost robotic Marie Antoinette of the rest of the trial disappears.

If I have not replied it is because Nature itself refuses to answer such a charge laid against a mother.

Standing to face the assembled crowd directly, she challenged them.

I appeal to all mothers here present – is it true?

Hébert’s time as witness here ends abruptly and the trial swiftly moved on. As far as it is possible to tell from the accounts, the reaction to Hébert’s revelation was not what he had expected. There was at best dismay and at worst a wellspring of sympathy for Marie Antoinette, especially from the mothers to whom she had appealed. Not that it mattered, of course. The trial ended the next day, and the following morning Marie Antoinette went to the guillotine.

Few figures in history have suffered as much as Marie Antoinette from the distorting influence of myths and lies. The very first thing that most people will say if you mention her name is ‘Let them eat cake!’, a cold-hearted and idiotic comment that almost certainly never passed her lips. But at least the last great lie in her story has never taken hold, and the myth of Marie Antoinette as child abuser was seen for just what it was. Revolutionary karma had an ironic sense of humour, and the old adage ‘what goes around comes around’ has never been truer than in this case. Less than half a year after Marie Antoinette’s execution, Hébert fell foul of Robespierre and was himself tried at the Revolutionary Tribunal. Legend has it he responded with far less dignity than Marie Antoinette, throwing his hat at his judges and trembling on the scaffold before a crowd clearly relishing every drop of irony. Fouquier-Tinville too fell from grace in 1795. He protested that “It is not I who ought to be facing the tribunal, but the chiefs whose orders I have executed. I had only acted in the spirit of the laws passed by a Convention invested with all powers.” His trial lasted 41 days, but ended in in the same journey to the guillotine endured by so many of those he had judged.

It is too easy to dismiss Marie Antoinette’s trial as an empty sham, too tempting to gloss over its details in the rush towards the tragic finale of her story. But to do so is to miss out on a rich insight both into Marie Antoinette’s character at this final stage in her life, and into the mentality and operation of a revolution spiralling rapidly out of control. Marie Antoinette remains a polarising figure, but whichever side you take, the squalid details of her trial and final days, and the unnecessary attempts to blacken the character of a woman already certain to die, serve as a chilling example of human cruelty.

Sources

Infuriatingly, there is no published account of the trial available in English. For this story I relied on a contemporary account published in The Times in 1793, and printed as a book under the title Authentic Trial at Large of Marie Antoinette, Late Queen of France, Before the Revolutionary Tribunal at Paris, published by Chapman&Co 1793. This is available to request at the British Library.