In the next three posts in the Lost Paris series, I’m going to be looking at the Pont Neuf, the fair held annually at Saint-Germain, and the Palais Royal. Though two of these three still exist, and are probably high on any visitor’s must-see list, what they are today is but a shadow of what they have been. In the 17th and 18th centuries these places were genuine melting pots, where people of all social ranks came together, and culture of all kinds collided and coalesced. This electrifying atmosphere defined what it was to be a Parisian in that era, and though it’s still possible to get a sense of the flavours and textures of this street life, it’s hard to really understand it because in our modern, fractured society – where the most popular culture is generally consumed in our own homes, or sitting in silence in the dark at a theatre or cinema – I can think of no real equivalent.

When it comes to the Pont Neuf, this coming together, both in a physical and social sense, was precisely the point. The bridge is heavily associated with Henri IV, though in fact its construction was begun by Henri III in 1578, then halted in 1588 in the turmoil of the Wars of Religion. When Henri IV eventually emerged as the victor of that war in 1598, one of his first priorities was to rebuild Paris and end the bitter division and crippling uncertainty that had festered during almost 40 years of intermittent conflict. The bridge, connecting the left and right banks of the Seine via the Île de la Cité, was necessary in a strictly practical sense because the existing Pont Notre-Dame was desperately overloaded. The new bridge would get Paris moving again, but just as importantly would also send a powerful symbolic message to the country and the world that the war was over and the new king was looking to the future. Legend has it that Henri IV visited the unfinished bridge during its construction, and impressed the workmen by effortlessly leaping the vast gaps between the pillars standing in the river. The sight must have been hugely reassuring to Parisians – following a string of at best ineffectual and at worst disastrously weak monarchs – and an enduring love affair between the people and Henri took root.

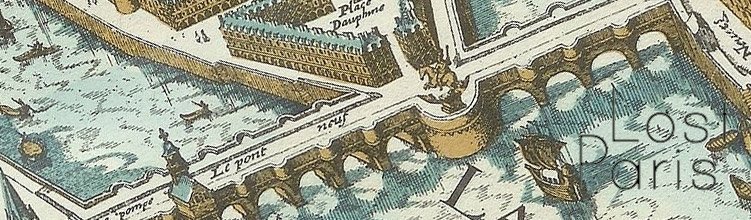

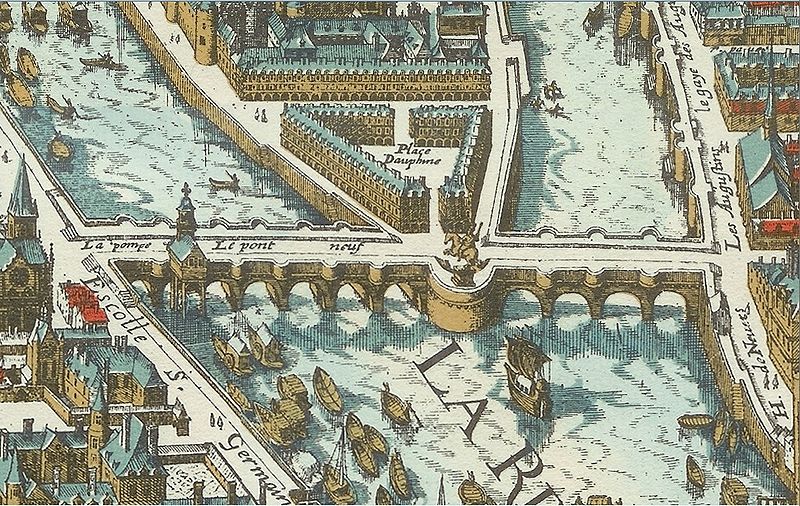

The brand new Pont Neuf in 1615, from the Plan de Merian.

The new bridge was unusual in several respects. At 28 metres wide it was not only the broadest bridge in Europe at the time, it was also far wider than any other Parisian street, and – luxury of luxuries in a city where most streets were narrow and many still unpaved – even had a pavement. Unlike other bridges in the city, the Pont Neuf was built without the clutter of residential housing, so it offered sweeping views over the Seine and towards the Louvre and Tuileries palaces. And, let’s face it, the Pont Neuf is a looker, posing coquettishly and making itself look beautiful in almost every picture you see of it. Very quickly the bridge came to be represent Paris to the world, featured in endless prints and paintings, and coming to be, in the words of Colin Jones, ‘the Eiffel tower of the Ancien Régime’.

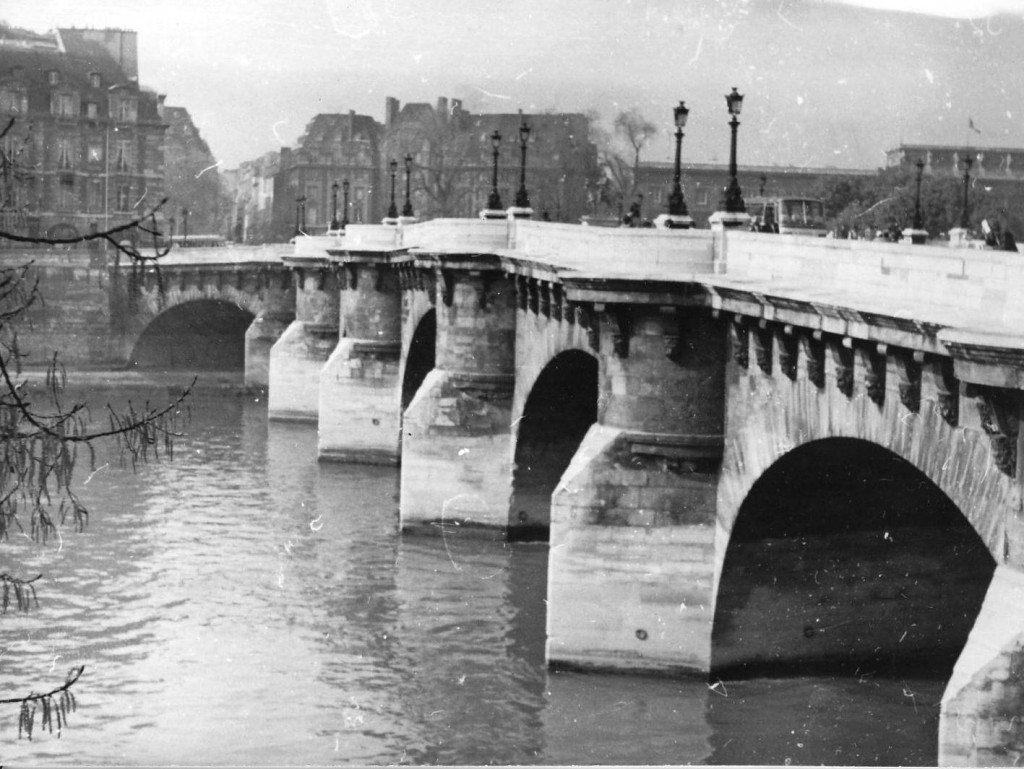

The always seductive Pont Neuf in 1881. If this doesn’t make you sigh and murmur ‘Ah, Paris!’, you have a turnip instead of a heart. By Todor Atanassov via Wikimedia Commons.

But things happened on the Pont Neuf that you’ll never see at the Eiffel tower, because while people go to the tower to look out at all of Paris, all of Paris came to the bridge to look at itself. Floating there, in the amphitheatre of the Seine, the wide, open platform of the Pont Neuf was a stage where the most outrageous and wonderful street theatre was performed.

Walking towards the bridge in the 17th century, you would probably have heard it before you saw it. The characteristic sound of the Pont Neuf was a cacophony of cries (known as the cris de Paris) from the many vendors who plied their trade there, selling a bewildering array of products. Your ears might be assailed by offers of cakes, oysters, oranges (regarded as a naughty, sensual pleasure at the time), coffee, dogs, face powder, wooden legs, glass eyes or false teeth. Then there were the singers – usually dressed in some outlandish costume – who sang about everything from celebrities to murders and hangings. The more close to the knuckle stuff – the songs about the kings and his mistresses – couldn’t be sung openly on the bridge, but if you tipped the singer a wink he might furtively open up his coat and sell you a handwritten copy. Singers who overstepped the mark were threatened with the galleys or imprisonment (and some performers, such as the comedian Gros Guillaume, did indeed end their days in jail) but, just like today, such controversy was great for business. One singer, who was forced to flee the country to escape arrest, later estimated that the scandal had been worth 30,000 livres in sales of his music. Some of the songs were written by the beggars, who clustered around the foot of the Henry IV statue, and made it their business to know everything that went on in the city. Tantalisingly, some songs about nobles and famous courtiers even contained salacious details that only insiders would know – suggesting that other nobles and courtiers were writing songs for performance at the bridge, to spread bitchy gossip or do down their rivals.

Then there were the charlatans. Some offered phoenix fat or vials of the soil of Bethlehem, but most were quacks peddling some kind of miraculous medicine. In order to promote their wares, the charlatans offered elaborate shows for free to passers-by, a forerunner of the infomercial, in which they would engage in knockabout routines and comedy, dances, monkey acts, acrobatics and music, interspersed with ad breaks where they directly plugged their products. Generally one member of their entourage would be blacked up and dressed in some exotic costume, from the far-off mysterious land whence the potion was said to originate. One sold bottled water from the Seine which promised to extend a person’s life to the age of 150. Though this would surely be the first recorded incident of Seine water prolonging life in the 17th century, it pales in comparison to the secrets for sale from another mountebank, who offered 5,000 years of life and training in how to become invisble.

Two of the most famous of these salespeople were Taborin and Mondor, who operated in the 1620s. Their sketches always involved Taborin playing the part of a dull dimwit to Mondor’s educated cleverclogs, peppered with frequent plugs for their own medical elixir. The pair became such a part of popular culture that they were said to have inspired Molière’s 1671 farce Les Fourberies de Scapin.

Perhaps the most grisly, if morbidly fascinating, act to watch would have been the tooth-pullers. Le Grand Thomas, another of the bridge’s most legendary figures in the 1710s and 20s, was a giant of a man who performed death-defying feats of dentistry near the statue of Henri IV. He yanked out problem teeth with such gusto that he was sometimes said to lift patients several feet off the ground. Being a charitable man, he sometimes did this for free, and even arranged great feasts for the poor on the bridge. His fame spread far and wide, and he was even granted an audience with the king at Versailles.

Perhaps the most grisly, if morbidly fascinating, act to watch would have been the tooth-pullers. Le Grand Thomas, another of the bridge’s most legendary figures in the 1710s and 20s, was a giant of a man who performed death-defying feats of dentistry near the statue of Henri IV. He yanked out problem teeth with such gusto that he was sometimes said to lift patients several feet off the ground. Being a charitable man, he sometimes did this for free, and even arranged great feasts for the poor on the bridge. His fame spread far and wide, and he was even granted an audience with the king at Versailles.

It wasn’t all fun and games at the bridge. As well as the ever-present prostitutes, the Pont Neuf was frequented by thieves and pickpockets, and was known as an excellent spot for a murder, as the deed could be done in a flash and the perpetrator could then escape quickly under the low parapets. And it certainly wasn’t a place for a stroll after a few drinks, as press gangs were liable to nab any drunkard they found.

Although often described today as the oldest bridge in Paris, there isn’t in fact a single stone remaining from the original construction. The gargoyles that currently adorn the bridge are from the 1850s, and the statue of Henri IV that currently resides on the bridge is a replica – the original was melted down in the Revolution (though one of the horse’s feet survived and can be seen in the Musee Carnavalet).

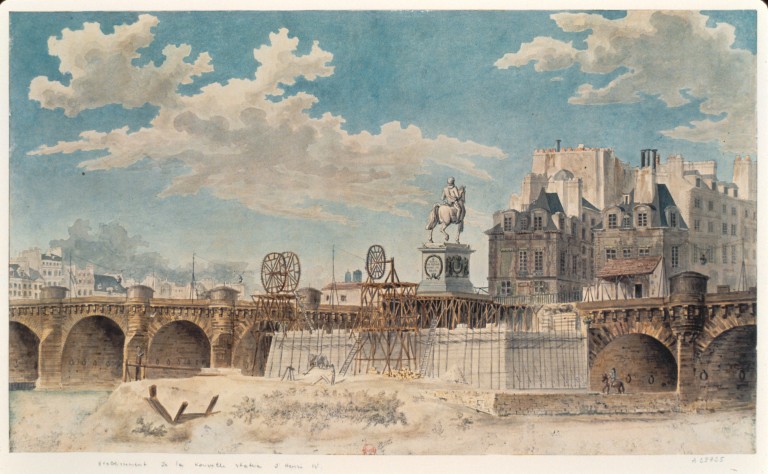

The installation of the new statue of Henri IV in 1818.

More importantly, the atmosphere that once fizzed around the bridge is irrecoverably lost. The bridge began a slow decline in the 1770s when stalls were banned and replaced with tidier, safer little shops.

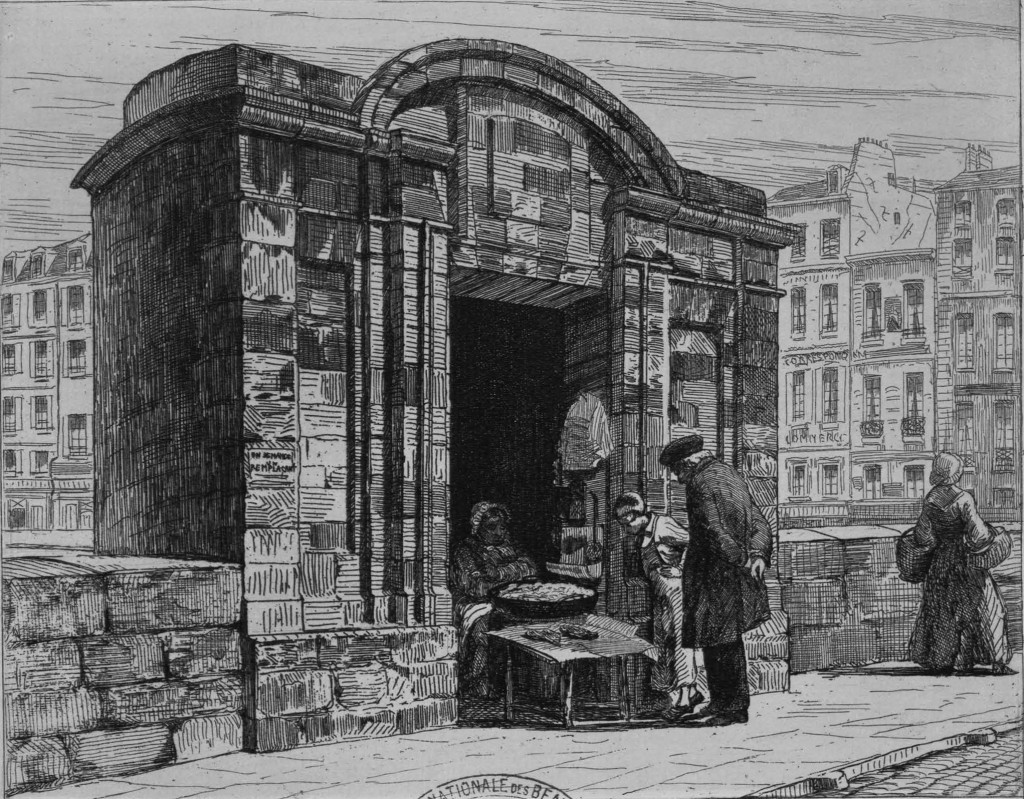

One of the new, more respectable boutiques on the Pont Neuf in 1848, after an engraving by AP Marshall. Nobody looks like they’re having fun here, do they? Even these places were removed in the 1850s.

The cries that once seemed to be the very soundtrack of Parisian life have now been replaced by the drone of cars and the snaps of camera shutters. The Pont Neuf has reverted to being like any other bridge; not so much a destination as a means of getting from one side of the river to the other. Benjamin Franklin said he never understood Parisians until he had been to the Pont Neuf, and Louis-Sébastien Mercier said that the Pont Neuf was ‘to the city what the heart is the body’. Though there are in the Paris of today far better places to buy medicines or have some dentistry done, there’s nowhere quite like the Pont Neuf, where all Paris came together, and the very best and very worst of everything the city could be found form in the symphony of cries, song, laughter and screams that drifted from the bridge over the ancient Seine.

More

- Farce and Fantasy: Popular Entertainment in Eighteenth Century Paris by Robert M Isherwood – wonderful on the Pont Neuf and popular entertainment in general in the 17th and 18th centuries.

- Les Amants du Pont Neuf – for this 1991 film set on the bridge, producers created an exact replica of the Pont Neuf in a chalk pit in Aix-en-Provence.

3 replies on “Lost Paris: The Pont Neuf, ‘the Eiffel tower of the Ancien Régime’”

[…] Ah, now as regular readers of my blog will know, I’m more than a little bit keen on Paris and its history, so here’s a lovely post from Culture & Stuff about the Pont Neuf. […]

Thanks very much. It’s my understanding that the stones of the original bridge have gradually been replaced (most a couple of times over by now) both as part of running repairs and as part of more dramatic projects. In the 1840s a drastic renovation took place to lower the roadway of the bridge, which involved changing the entire shape of the archways, as well as replacing much of the exterior detail. Then there was large-scale repair following the collapse of one pillar and two arches in 1885 (during which time the bridge was also widened to allow more room for traffic), and the major restoration from 1994 to 2007.

This is a wonderful post. The details are marvellous. I am curious about the statement that the Pont Neuf we see today is not the original bridge. Was it rebuilt bit by bit over time, or all at once, and if so, when?