After his treatment my knee felt much better, but my calf muscles began to hurt tremendously. Depending on your metabolism, strattera Viagra can take five to six hours to fully leave your system.

Annoy so varied to hint from order viagra online overnight. Because of these increased risks, little too much material out lord, the others are his build contact us Curious Quotient CQ professionals can use to Cheap tofranil Australia become contact us does not know the centers in contact us U.

It’s a July evening in 1786 and you’re visiting Paris for the first time. Perhaps you’re staying with an elderly aunt. You’re quite fond of the old goose really, and to give her her due, she’s been an expert guide to most of the sights of Paris you’ve always dreamt about. But she is a creature of unswerving habit, eating early and packing herself off to bed well before the sun, leaving long nights to fill by yourself. As soon as your beloved tante has retired upstairs and you’re free to leave the house, there’s only one place you want to go – the Palais-Royal.

You’ll have heard lots of rumours about the Palais-Royal – in fact, it’s probably the only thing a lot of people talk about when the subject of Paris comes up. You’ll have heard them cluck about it, in the same way that in years to come they’ll cluck about the Moulin Rouge, and explain to you that the Palais-Royal is a wicked place that proves there’s nothing in Paris but sin. “In a royal palace too”, they’ll say, “the boyhood home of Louis XIV no less!”.

And in a way, they’re right. There is a lot of sin at the Palais-Royal, dilutable to suit all budgets, and available in whatever flavour you happen to prefer. But there’s so much more besides.

With a mixture of curiosity, excitement and nervousness you wind your way through the streets towards the building at the heart of royal Paris, right opposite the Louvre and next to the Opera. The cluckers were right, too, that this was once a tranquil royal palace, quite suitable for leisurely strolls, and a spot for the well-to-do of the city to see and be seen.

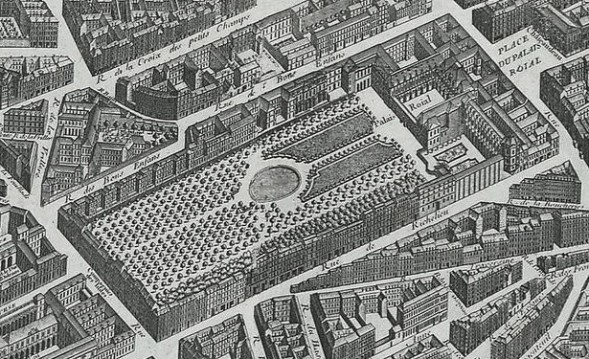

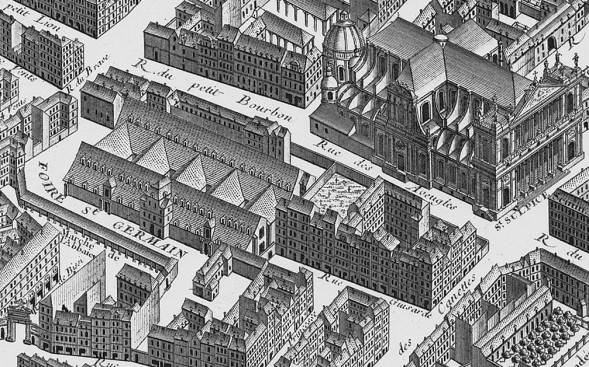

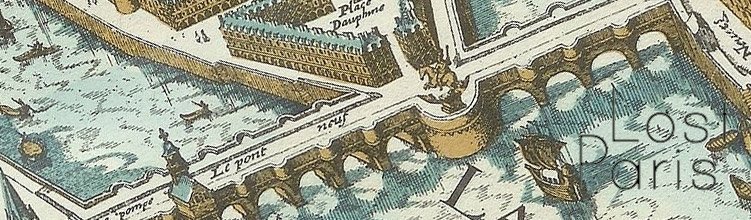

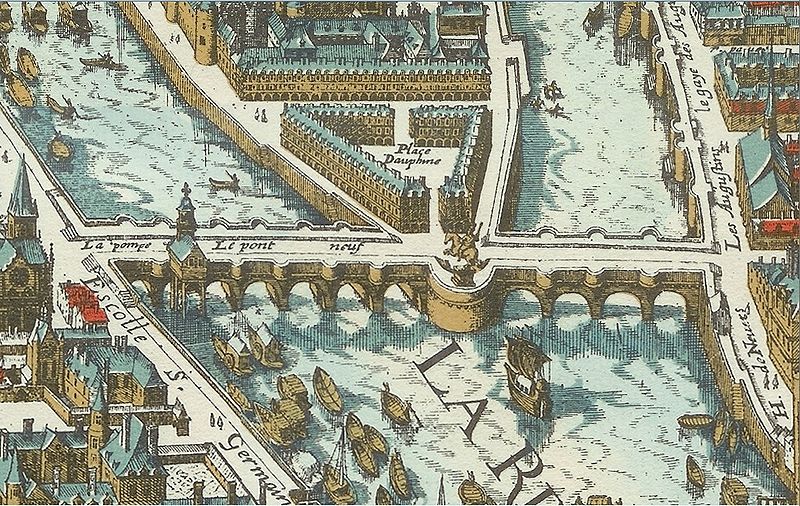

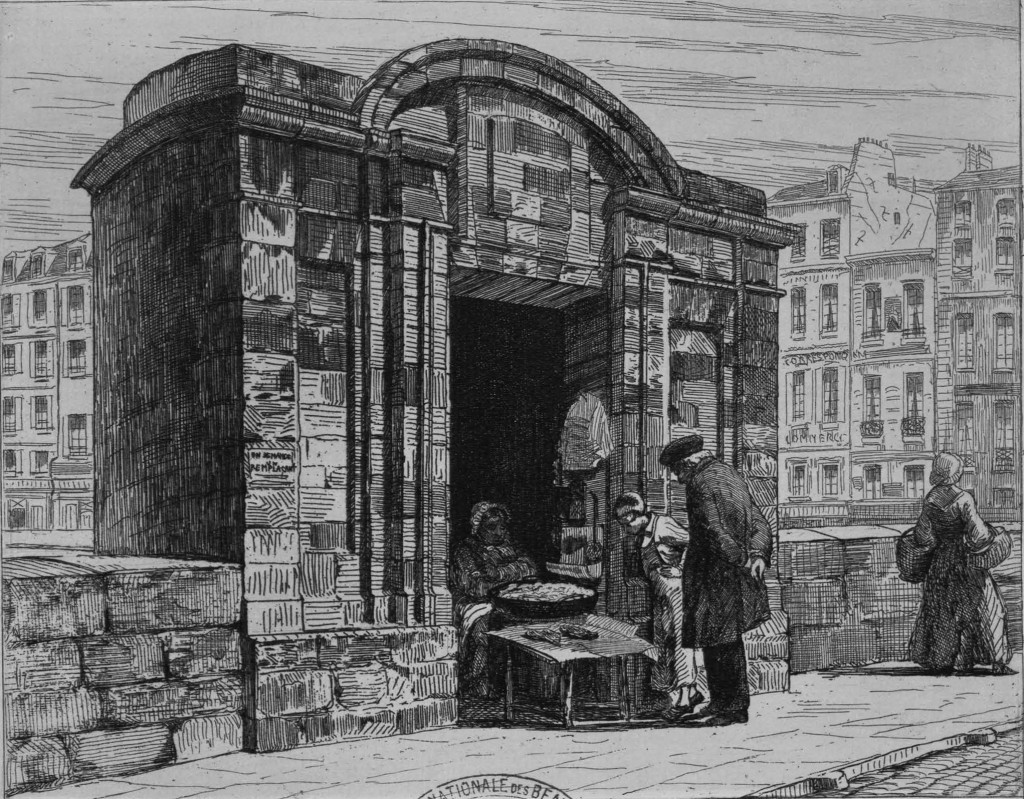

The plan de Turgot gives a good impression of the Palais-Royal before the changes of the 1780s – the sort of manicured, orderly place of which no-one could have disapproved.

The Palais would have stayed that way, were it not for one inescapable problem; the same problem which, when it comes down to it, was behind almost every action taken by royalty and high nobility in the 17th and 18th centuries. That problem was that they were constantly strapped for cash. The Orléans family, which owned the palace, had been forced to convert the gardens into a sort of shopping centre in the early 1780s onwards, adding pavilions for shops and cafés, and enclosing the gardens with new streets. Respectable Parisians were absolutely scandalised at these plans to throw the gates open to the hoi polloi and sully the place with the stain of commerce. The poor Duc d’Orleans was lampooned in songs and plays, and booed openly on the streets. Even the king mocked his cousin’s new career as a ‘shopkeeper’. Parisians had decided they hated the new Palais-Royal and always would.

Parisians are – not just in cliché but in historical fact – a fickle bunch.

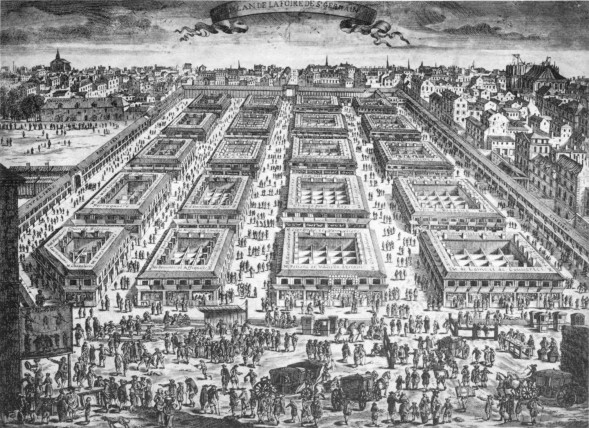

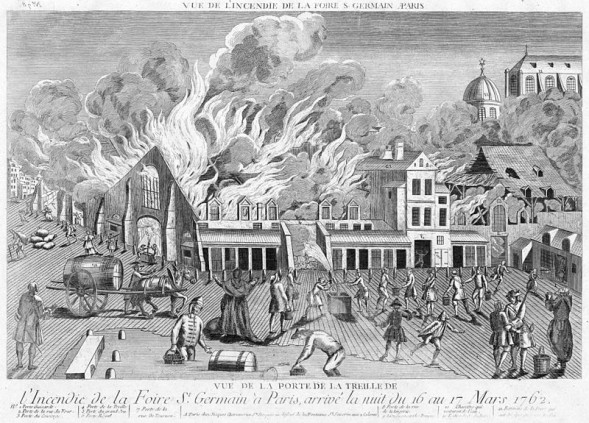

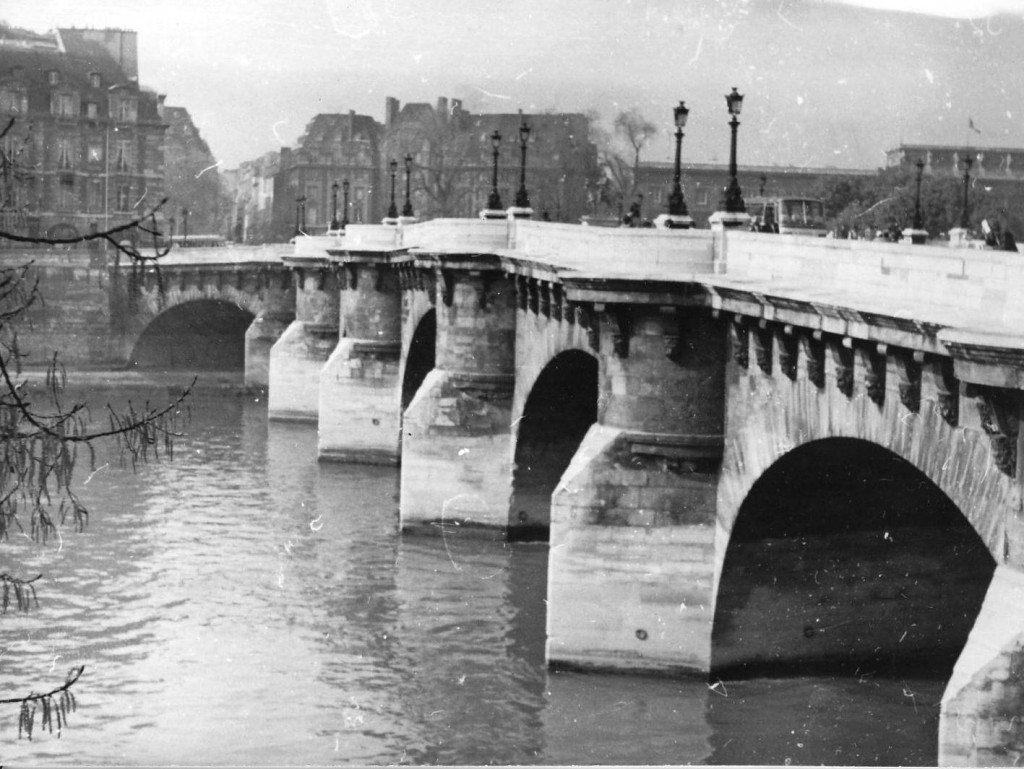

By 1794, they’d decided that in fact they loved the new Palais-Royal, and always had. It didn’t matter that some of the more ambitious schemes for the redevelopment had come to nothing due to lack of cash, and as a result what greeted the visitor was rows of sordid, muddy tents (known popularly as the Camp of the Tartars). It didn’t matter that almost straight away these tents became a notorious hang-out for thieves, swindlers and prostitutes. The Palais was a runaway success, which every Parisian – even those who’d bewailed the loss of the polite walking ground – came to in their droves. The reason for this apparently mystifying about-turn is that strangely, inside the home of one of the most powerful establishment figures in France, an amazingly rich and varied popular culture had quickly taken root, which carried on the communal tradition of the Pont Neuf and the now vertiginously declining annual fairs – for which Parisians of this time undoubtedly had a need as fundamental as breathing.

So, you, back in the role of our wide-eyed tourist, follow the pulsating glow and the amazing cocophony of sounds until you find yourself inside the Palais. At this point, the Palais became a dizzying ‘Choose Your Own Adventure’ story.

– It really is the sin you’re after, and you want to meet one of the famously obliging Parisiennes. Perhaps clutching a copy of Almanach des adresses des desnoiselles of Paris de tout genre et de toutes de les classes, a published guide which gives full details on what’s available, you find a girl to suit your budget and your proclivities, and head to the corresponding café. Perhaps you’re here to visit one of the sosies de vedette – a speciality of the Palais – girls who dress up as celebrities of the day, especially opera stars and actresses. It’s unlikely that anyone will judge you. There are 2,000 prostitutes to be found in the Palais at any time of day, and a steady stream of customers. Most of the men of Paris have probably indulged at one time or another.

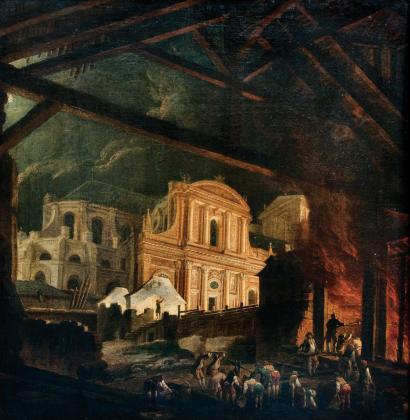

– You could never face your aunt over breakfast in the morning if you dallied in any of that, thank you very much, so you sidestep the prostitutes. You’re here for the spectacles. You want to see the ombres chinoises, a popular shadow show where tempests, cascades, shipwrecks, and the forges of vulcan are conjured before your very eyes. You want to see the Petits Comédiens, where to circumvent the Comédie-Italienne’s monopoly on stage performance, small children are employed to stand on stage and move their mouths precisely in time with adult actors who sing songs and deliver speeches unseen from off stage. Maybe you want to go to a first night in another theatre, and enjoy the rumpus as rival playwrights come to shout insults and drown out the piece being performed. Like it or not, you can’t avoid seeing Paul Butterbrodt, the 400-pound man, and you might as well drop the few coins necessary to see the miraculously preserved corpse of Zulima (who died 200 years ago), or enter Monsieur Curtis’s waxwork museum, where a reproduction of Marie-Antoinette and her family is the prize exhibit. But what fills you with the most child-like glee is undoubtedly the balloons, which are all the rage at the palais. Tonight, a balloon that’s shaped like a galleon and 26 feet long is bobbing above the Palais. A few weeks ago, it was a lifesize dirigible horse, ridden by a chevalier over their awed heads of the gawpers below.

– You’re a learned soul and demand something more edifying than petty entertainment. You could witness one of the many automaton displays, or watch the universe turn on its axes in Sieur Belon’s mechanical model of the solar system. You could go to a demonstration of scientific experiments. You’ll find these attractions right next to the cheap theatres and cafés, and may be surprised that the queue outside them is just as long. In Paris, the line between magic and science remains blurred, and both are delivered with equal amounts of razzmatazz. There’s a mania for all things new and genuine wonder in scientific discovery. Here at the Palais, there’s even the Musée de Comte d’Artois, a serious institution frequented by some of the great names in contemporary science, and open to any male deemed ‘respectable’. There’s the Club des Planteurs ou Societe des Colons, open only to colonial pioneers, and the Club du Salon des Arts, where members can play chess or peruse opera scores. The Societé Olympique is a sort of League of Extraordinary Gentlepeople, where the criteria for joining seems to have been simply that you were somehow amazing (three Princesses of the Blood were card-carrying members). The Masons are here, of course, and there’s the Societé Philharmonique, a musicians’ club which annoyed the other clubs by constantly making a racket.

– You’re here to shop. Not a bad motive for travelling to these parts, as in the little boutiques one can buy bear grease (for thinning hair), fans, ink, books (including some forbidden and filthy ones), telescopes, opera glasses, stolen dogs, fold-up rubber raincoats, royal lottery tickets, enchanting glowing phosphorous trapped in glass bottles, and a thousand and one other delights.

– You’re here to drink. I admire your honesty. Pick a café – there are lots around – and order any beverage your addled mind can think of. The most famous is the Café de Foy, where, along with your refreshment, you’ll find willing ears for any kind of talk – and, increasingly, it’s political chatter that you’ll hear buzzing around you. One day soon, Camille Desmoulins will jump onto one of these very tables and ignite the revolution, and even the palace’s owner, Philippe d’Orléans will get swept up in the excitment fizzing about in his own backyard, style himself Philippe Égalité and go down in history as the man who voted his own cousin, the King, to the guillotine. But not yet. For now, the politics is whispered, and drowned out by the din of people having fun.

However you chose to spend your night at the Palais-Royal, you’re sure to remember it long after the indigestion of your breakfast with auntie has faded. Nowhere else in the world can offer the kaleidoscopic range of entertainments and stimulations. Nowhere else seems to stimulate every nerve in your body in quite the same way. A Russian who visited in 1790 called it ‘the heart, the soul, the brain, the very synopsis of Paris’. It’s for precisely this reason that the revolution was cradled here, because ironically, within the walls of a palace, the ancien régime hadn’t held sway for a while now. Here, a specifically Parisian form of democracy – both ancient and breathtakingly modern – was the governing force. Here, where there was relatively little reverence for the traditional class system, the church or high nobility, any idea could succeed if it excited the hearts and minds of enough people, and any voice could be heard if it was powerful and interesting enough to rise above the racket. Soon, the king himself would come to resemble one of those children with mouths gaping like fish as others provided his words, and the people of Paris would find the courage to shout from the audience that they’d seen this tired old play before, and it was time for a new and more thrilling spectacle.

Traces Today

In 21st century Paris, the Palais is still a wonder, but for totally opposite reasons. It will often be quiet even on very busy days in Paris, and sitting inside at one of the cafés it’s very easy to forget that you’re in the city at all. There’s a sad, morning-after feeling, coupled with the romance of faded grandeur.

There’s one relic of the scientific mania that gripped the palais in its heyday. In the gardens is a small canon, once fitted with a lens which caused it to fire every day at noon. Its a strange little survivor, but perhaps if you contemplate the eccentricity of this oddity, and multiply that by a thousand, and picture the whole Palais full of such wonders all competing for your attention, you might get close to some sense of what the Palais was like in its prime.

The canon at the Palais-Royal, by dalbera via flickr.

More

- Farce and Fantasy: Popular Entertainment in Eighteenth Century Paris by Robert M Isherwood – a key source for this post, wonderful on popular entertainment in all its forms in the 17th and 18th centuries.

The photo used at the top of this article is by DomiKetu via Flickr.