February in medieval Paris can’t have been much fun. When the sun went south for the winter, the city must have been a gloomy place, returning to its prehistoric origins as a swamp (the city’s Roman name, Lutetia, derives from lutum, Latin for mud, according to one persuasive theory) and life for your average Parisian must have been painted an unappealing shade of dull, dirty brown. So it was with great excitement that the people of Paris awaited the coming of the annual Saint-Germain fair – quite literally a burst of light in the darkness, and an intoxicating, sensual shot in the arm to see them through to the first days of spring.

In this picture of the fair, a miniature painted by Louis-Nicolas van Blarenberghe in 1763 now in the superb Wallace Collection, it’s the beautiful, warm light that draws you in to a world of wonders and theatrically illuminates the many spectacles of the experience. It’s one of those paintings you just want to jump into.

Together with religious festivals, the great fairs formed the foundations of the social life of the city in the medieval and early modern period, and, like the giddy thrill of a walk on the Pont Neuf (see my last post), almost everyone in Paris would at some stage have attended the fairs, the grandest rubbing shoulders (and quite possibly other body parts) with the humblest. There were two key annual fairs in Paris, the Saint-Germain (on the same site as the present covered market, off the Boulevard Saint-Germain), which first appears in the record in 1176, and the Saint-Laurent (roughly where the Gare de l’Est is today), its younger brother born in 1344. The Saint-Germain fair was traditionally open from 3rd February until Palm Sunday, and the Saint-Laurent from late July until the feast day of Saint Michel in September, though both were frequently extended. Though both fairs were popular, the Saint-Laurent was more well-behaved and respectable and less fun, and if you gave any Parisian the choice between the two they’d always plump for the Saint-Germain – and it’s this one I’ll be focusing on in this post.

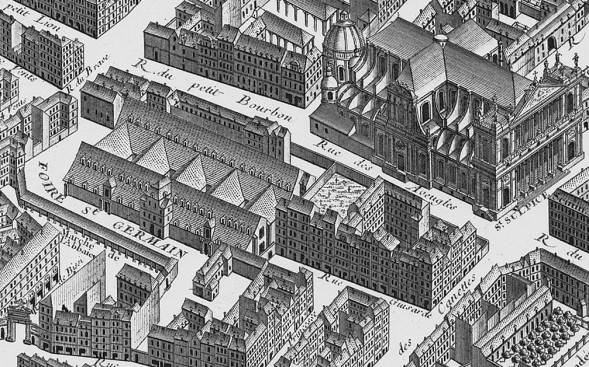

View of the fair in the Merian (1615) and Turgot (1730s) maps of Paris.

Both fairs were started by monks in the middle ages less as entertainments than as a means of providing shelter and sustenance for pilgrims who came to honour the abbeys’ relics on particular days in the church calendar. Saint-Germain-des-Prés holds a particularly interesting place in the history of the city, existing as almost a separate entity from the rest of Paris up until the late 17th century. In the medieval period, the Abbey was outside the walls of the city, and owned a huge chunk of the land on the left bank, corresponding today to an area from the Luxembourg Palace to the site of the Eiffel Tower. The abbots were powerful feudal lords, usually with royal blood, and like other abbeys in the city, Saint-Germain was outside the jurisdiction of the Parisian authorities. Not only that, but the entire abbey was surrounded by a great ditch and a thick, fortified wall, making it essentially its own little world where interesting and unusual activities flourished. The long arm of Parisian law did not stretch as far as Saint-Germain (which had its own courts, prison and gallows), so opportunistic criminals could seek refuge here and escape punishment if the monks proved amenable (and, one gets the impression, the monks of Saint-Germain could be extremely amenable if their palms were crossed with sufficient precious metals). The powerful and usually ultra-conservative guilds that controlled all arts and crafts in the city also had no influence in the abbey, which meant that the abbey benefited from the creative juices of talented foreign artists, who were forbidden to work in Paris proper by the guilds.

The Saint-Germain fair was perhaps the most visible and wonderful manifestation of this strange jurisdictional bubble -a topsy-turvy world of indulgence, liberty and -yes – sin, which would have been frowned upon by Parisian society under normal circumstances, taking place not only in the shadow of one of the most holy churches in France, but in Lent no less! To understand what the fairs became once they moved away from merely serving the needs of pilgrims, it’s necessary to comprehend the curious doublethink that defined society in the early modern period, especially I think in Paris. This was a world at once still bound to religion and fearful of hell and damnation, and yet highly attuned to the fragility of life and the ever-present spectre of death, willing to mine every rare opportunity for every ounce of pleasure it would yield. It was also a very outward-looking society, fascinated by the new world opening up and the undreamt of wonders it contained, as well by rapid developments in the sciences. In the 17th and 18th centuries, the horizons of knowledge and exploration seemed unlimited – anything, suddenly, was possible, and excitement over every new discovery created a feeling of liberation, rather than the weighty, nagging knowledge of everything we don’t and can’t know which can often bog down the popular perception of science today. Parisians were hungry for the new – to see it, taste it, show it off – and the Saint-Germain fair offered them the chance to do just this.

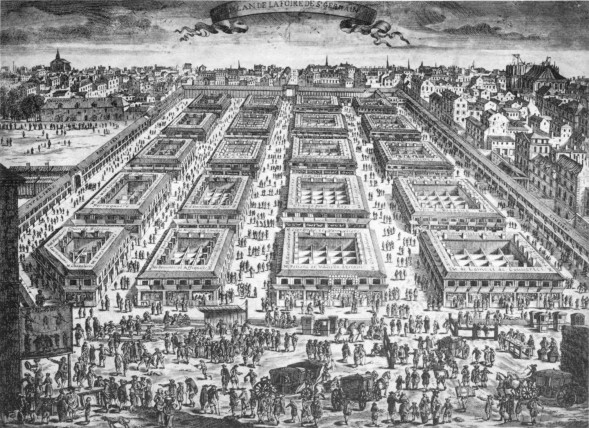

A view of the fair in the 18th century, by Jollain.

Let’s visit the fair in the 17th century. By now, it covers a huge area and its centre is two huge pavilions, spanned by a roof and sunk 6 to 8 feet into the earth. Simply entering these strange subterranean palaces could be a challenge, but thankfully there was generally such a crush of people cramming in alongside you that it would have been impossible to fall over. As your eyes adjust to the glow of lamplight, your nose begins to detect ripples of wonderful aromas. Almost everything you could dream of eating and drinking was available here – delicate pastries, pungently spiced breads, jams, waffles, fruit, confections, beer, hard cider, hippocras and eau-de-vie. If you can pick them out in the crowd, you might be able to buy a coffee from the two Armenians who worked the fairs from the early 1670s, or an exotic liquor infused from herbs and spices from Francesco Procopio dei Coltelli, the Sicilian who in 1686 will parlay his success at the fairs into his very own establishment that will one day be known as the the Café Procope.

If you’re not in need of a nap after all those treats,and fancy some shopping, you can buy anything and everything a chap can unfold (excuse my Bedknobs and Broomsticks reference) at the market. You can see some of them in the miniature above – glinting Venetian mirrors, paintings and sculptures, together with heady perfumes, moroccan leather, gloves and knives. The paintings were often created by the artists working under the protection of the abbey, free from the guilds of Paris. The only problem was, in order to get their paintings from the abbey to the fair, the artists had to cross streets that were under the jurisdiction of the Paris guilds, whose heavies could stop them and seize and destroy their work. This led to elaborate subterfuge and smuggling, and a constant battle between the artists and the guilds. You could also, increasingly in the 18th century, buy popular optical devices and mechanical automatons to experience the wonders of modern science for yourself, and impress your friends.

A finely balanced and at times symbiotic ecosystem existed at the fair in which every desire of the visitor could be catered to the very instant he became aware of it, and money flowed liquidly from hand to hand, circulating round the pavilions in great tides and whispering eddies. So if gambling tickles your fancy tonight, you can put a coin in someone’s pocket and try your luck at cards or dice, or on the spinning wheel. If you’re lucky enough to win (the games are often rigged), there’s always a thief on hand to cut the fabric of your pocket and relieve you of the burden. Flush with his success, the thief decides to stroll towards the cabarets. On the way he walks past the little theatres, each with their own balcony outside where the actors put on free shows as a sort of a trailer for what can be seen inside (which again can be seen in the miniature). Tight-rope walkers teeter on ropes overhead, and acrobats shock the unwary by leaping suddenly and dramatically into the air. The thief stops at an animal attraction – not, this time, the ‘scholarly’ deer who can guess people’s age, or the rats trained to do ballet, or the ‘white bear from the icy sea’ from Monsieur Ruggieri’s menagerie – but a monkey playing the hurdy gurdy which caused a great sensation at the fair. The thief throws a coin into a tin and the monkey begins to play an allemande very elegantly, then someone throws a nut and the creature scampers away to get it, but the music keeps playing. The thief yells at the charlatan keeper of the monkey for duping him, and gives chase, knocking over the tin and scattering his takings. A group of well-to-do boys pounce on the coins and run off to see one of the puppeteers – some so good they’re rumoured to be magicians commanding the devil’s minions – and thus the stream of cash continues to flow around the fair.

Perhaps what’s most surprising about the fairs is the degree of sexual permissiveness to be found there – which is more commonly associated with later periods in Paris’s history, and we’d blush at even today. Prostitution mainly centred around the cabarets, where sexual encounters took place on a large scale, and openly in booths, or in rooms rented our in nearby houses. The cabarets were frequently in trouble with the police and commissaires charged with the impossible task of keeping order at the fairs, but they never succeeded in shutting them down.

And yet, with all the chicanery, fights and prostitution, the fairs remained a respectable place for all classes of society to go – even high-ranking ladies could be seen there, turning a blind eye to the insults thrown by commoners as they jostled in the crowd. At the fair, the line between fantasy and real life was wilfully blurred – rules were left at the walls of the abbey and theatre spilled out onto the streets.

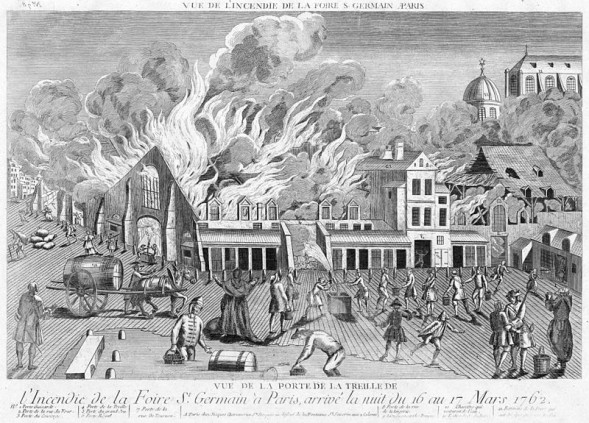

In the 18th century, the fairs, which had entertained Parisians for 600 years, began to decline, and this was hastened by a fire which destroyed the fair at Saint-Germain in 1762 – a blow from which it seems never to have recovered. Something of the spirit of the fairs was maintained, however, and found a new home at the Palais Royal – which I’ll be exploring in my next post.

The fire of 1762, from a roughly contemporary engraving

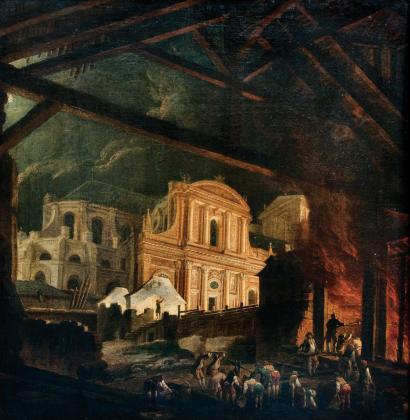

Another view of the fire, from a painting by Pierre-Antoine Demachy which recently sold at auction in Paris. Thanks to reader Marc Philippe for telling me about this.

More

- Farce and Fantasy: Popular Entertainment in Eighteenth Century Paris by Robert M Isherwood – many of the details of the fair come from this fantastic account.

- Paris in the Age of Absolutism by Orest Ranum – very strong on the intricate politics and culture of the city in the age of Louis XIV.