There aren’t many things I’m good at doing if I’m suddenly woken up from sleeping. Operating a pair of trousers is a challenge, walking in a straight line a chore, and conducting a meaningful conversation a scientific impossibility.

I don’t want to become one of those web sites that worship the ground Marie Antoinette walked on, but on this most basic trouser-operating, conversation-having level, Marie Antoinette was something of a god. On that bitterly cold night, on 12th October 1794, the former queen was woken and taken from her cell to the Great Hall of the Revolutionary Tribunal. The room was inkily dark – only two candles flickered in the large space – making it more or less impossible to determine how many people were in the room, who exactly they were, or which shadow was speaking at any one time. Eventually, the figure of Antoine Quentin Fouquier-Tinville, the President of the Tribunal, emerged out of the gloom. Fouquier-Tinville had already earned himself the reputation as one of the Revolution’s attack dogs, having conducted the trials of such revolutionary bête noires as Charlotte Corday (Marat’s assassin) and many other less famous unfortunates. Totally ruthless in pursuit of revolutionary justice, legend had it he slept with an armed guard at his door and a hatchet under his bed, for fear of the people he was sworn to protect.

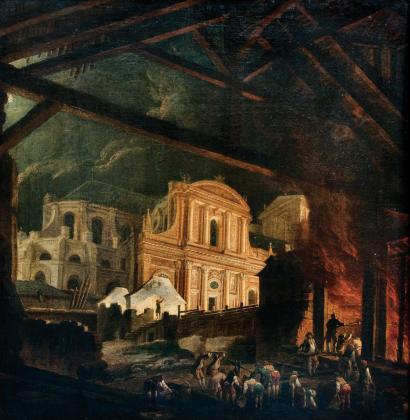

Antoine Quentin Fouquier-Tinville

Fouqier-Tinville was not an easy man to square up to at the best of times, and these were not the best of times. Marie Antoinette arrived in the chamber for the secret interrogation having no prior knowledge that it was to take place, much less what would be asked of her. She had no legal counsel of any kind, and was utterly alone in the room. She had been imprisoned for many months; both her mental and physical health were as low as they had ever been. But if nothing else, Antoinette was a performer, and in the secret interrogation she turns in the performance of a lifetime.

The entire purpose of the secret interrogation was to try to obtain evidence that could be used against Marie Antoinette in the trial. There was of course no opportunity to plead the Fifth here. As we shall see, though Marie Antoinette’s guilt was pre-determined and already certain in the minds of almost everyone in France, the actual case that had been assembled against her was in most particulars very far from impressive. Fouquier-Tinville, in short, needed Marie Antoinette to slip up here, to give something away under pressure – hence fetching her in the middle of the night, hence the darkness, hence the lack of ceremony and quick-fire questioning. stromectol pret farmacie

Who knows if Marie Antoinette had decided her gameplan at some point previously, or if it came to her on the spot, but her approach (as it will be throughout the trial) is to remain matter-of-fact to a level which is almost robotic, to never rise to bait or give emotional answers, and to be as brief as possible. This is an especially clever tactic in contrast to the hyperbolic, hysterical fervour of her accusers. Though it was always likely to be construed by her enemies as yet another example of her legendary coldness, it provided her with a solid emotional compass to guide her through the most dramatic moments of the trial. Perhaps we can even go further – perhaps this is the stance of a woman who deep down knows that her death is coming, and has determined to deny every possible ounce of satisfaction she can to the people who will exact it.

Without losing sight of her overriding tactic, the former queen never capitulates or gives an inch, especially where matters of pride are concerned. Early on, when asked where she had been when she was arrested, she responds that she has never been arrested, but has simply been conveyed to her various prisons (p10) – a technicality, perhaps, given her current situation, but one which clearly matters to her.

There’s little in the accusations wheeled out during the secret interrogation that’s likely to have come as much of a surprise to Marie Antoinette. What might have been more shocking though is the manner in which the accusations were put to her. Even in the past few years, in her private life at least Marie Antoinette had remained relatively shielded from open disrespect or scorn, especially as she always seems to have worked some kind of softening magic on the people who served her. Although the secret interrogation does not rise to the theatrical heights of venom and rage unleashed in the trial itself, her accusers are openly confrontational and superior, and certainly display not a shred of the awed deference with which she had been treated throughout her life as a princess and queen. This was not something she was accustomed to.

The old accusations are trotted out one by one, beginning with the belief that Marie Antoinette provided money to Austria to fund a war against the Revolution. This she flatly denies, and points out astutely that ‘my brother did not want money from France’, which doubtless had none to give anyway. When accused of holding ‘secret and nocturnal petty councils’ (in the language, very reminiscent of witchcraft, which is a feature of the trial) with her supporters, she boldly replies that “the rumour of those committees has constantly existed whenever it was intended to amuse and deceive the people”. Then, when accused of ignoring the entreaties of the “then minister of justice” Danton in November 1791, Marie Antoinette makes a factual correction, saying Danton was not the minister at that time (p12).

Her answers betray an extraordinary amount of self control, clearly holding back very real anger which sometimes nearly breaks through before being reigned in again, as in this exchange (p12-13).

TRIBUNAL

Observed, that it was she who taught Louis Capet that profound dissimulation by which he has for too long deceived the kind French nation, who did not believe that perfidy and villainy could be carried to such a degree.

MARIE ANTOINETTE

Yes, the people have been deceived – cruelly deceived! But it was neither by her nor her husband.

TRIBUNAL

By whom, then, has the people been deceived?

MARIE ANTOINETTE

By those who felt it their interest; that it has never been theirs to deceive them.

Marie Antoinette quickly dismisses questions over the royal family’s escape plan by sticking to what was always the family’s official line – that they had never intended to escape France, but rather to find a safer part of it and “conciliate thence all parties for the happiness and tranquillity of France” (p13). Even the most ardent Marie Antoinette fan would have to concede this comes over as a little disingenuous, but bafflingly, the point is not pressed. Instead, her accusers move on to the seemingly trivial and obvious question of why she adopted a false name during the escape.

The former Queen’s cold, emotionless approach occasionally borders on irony, giving away her withering contempt for her questioners. In perhaps my favourite of her answers during the trial (when she is again being pressed on the matter of being the ringmaster of the escape plan, and the fact that she opened a door at the Tuileries and made everyone go out), she replies that she “did not believe that the opening of a door could prove that a person directs the actions of another” (p14).

Her prosecutors push further (p14).

TRIBUNAL

Observed, that she never concealed for a moment her desire of destroying liberty; that she wanted to reign at any cost, and re-ascend the throne upon the corpses of the patriots.

MARIE ANTOINETTE

That they did not want to re-ascend the throne: That they were upon it; that they never had any other desire but the happiness of France. Be it happy: be it but happy! they would always be contented!

Somehow the spare third person of the trial record seems to heighten the drama of these exchanges, and draw out the tension between what is being said and what is being so carefully not said.

The prosecutors then move on to the question of whether Marie Antoinette had been in contact with the enemies of the Revolution, both foreign and the emigrated princes, and provided them with vital military information. This is probably Marie Antoinette’s most vulnerable point; there are reasons to believe she may have actually done this, and she clearly falters here (p15). goedkoop ivermectina

TRIBUNAL

You have held a correspondence with ci-devant French princes since their quitting France, and with the emigrants; you have conspired with them against the safety of the state.

MARIE ANTOINETTE

She never held any correspondence with any Frenchmen abroad; that with respect to her brothers, she might have written them one or two insignificant letters; but she does not believe she has; and recollects having often refused to do so.

Despite the fact that her confidence clearly deserts her here, and the answer she gives is evidently inadequate, this is remarkably not followed up, and the subject is immediately changed, leaving important questions unasked. If she has often refused to write letters, for example, who was trying to make her? Here, the crippling lack of evidence against Marie Antoinette is exposed, with the consequence that her accusers have no trump cards they can use to force more out of her. It simply comes down to their accusation versus her denial.

There are further telling moments, as when Marie Antoinette is asked (p16)… pyrantel ivermectin horse wormer

You regret, without doubt that your son has lost a throne, which he might have ascended, if the people, at length enlightened upon their true rights, had not themselves crushed that throne?

MARIE ANTOINETTE

She shall never regret anything for her son, as long as her country is happy.

She seems to find strength in this simple strategy of insisting her only aim was the happiness of her country, and it’s one she holds to time and again in the trial. Indeed, her confidence seems to grow as she realises the paucity of evidence available to her prosecutors. She even goes so far, when challenged on rumours that she was kept in constant communication with the outside world whilst at the Temple, that “those who declare anything of the kind, dare not prove it” (p17).

The secret interrogation comes to an end without having obtained any killer evidence, or indeed anything much of real significance that can be used in the trial. In a poignant moment, Marie Antoinette is asked whether she needs to have counsel appointed by the court for her trial, and she replies that she does, because she ‘knows not any one” (p19).

Tronson Doucoudray and Claude Chaveau-Lagarde are named as her lawyers. Chaveau-Lagarde was perhaps a likely suspect for this job, having already established something of a reputation for defending revolutionary hate figures, including Charlotte Corday, Madame Roland, Jean Sylvain Bailly and several moderate Girondins. Showing great courage, and attracting all kinds of the wrong attention to himself at a time when blending into the background was by far the safest option if one wanted to remain attached to one’s head, Chaveau-Lagarde provided that basic legal support permitted to lawyers in the Revolutionary Tribunal, in cases which everyone knew were hopeless.

Marie Antoinette returned to her cell knowing that her trial would begin in just two days. Unlike her husband, who had been given weeks with his lawyers to prepare his defence, Marie Antoinette would have less than 24 hours, during which time they were not even aware of what charges were to be brought against her, and would have been under constant surveillance. Her lawyers would not be permitted to speak for her in court, so it is likely that in whatever time they had available their advice would have been more general, on how to stand up to the coming onslaught (of which the secret interrogation been just a taster), and how to frame her answers. Perhaps, with their hands tied so firmly behind their backs, the lawyers’ real contribution was psychological and supportive more than it was detailed or practical. In any event, when the trial began it would become clear that Marie Antoinette would hold to the instinctive course set in the secret interrogation, and was more mentally prepared for the key lines of questioning revealed during this ordeal. In some crucial ways, then, the secret interrogation had been far more beneficial to the former queen than it had her accusers.

Next time: the trial proper begins.