In the last part of the guide to Marie Antoinette’s trial, I looked at the way she dealt with the completely unexpected and totally secret interrogation which was sprung upon her two nights before the trial proper was to begin.

The challenge that faced her on the morning of 14th October was very different. This time there was no dark chamber populated by a few shadowy figures. This time the Great Hall of the Revolutionary Tribunal had been transformed into the great political theatre that was in many respects its prime function, and it quickly became clear that this performance would be standing room only. Every available seat was taken, most picturesquely by the infamous tricoteuses – a gang of ardent women, like some sinister version of Donny Osmond fans, who attended so many trials and executions that they now bought their knitting with them to help pass those interminable moments waiting for the delivery of a verdict or the fall of a guillotine blade. The atmosphere was probably something akin to a circus, with refreshments on sale and lively, expectant chatter – especially as most of the Revolution’s darlings, including spidery Robespierre and hogheaded Danton, were in attendance. Fouquier-Tinville, who would be familiar to Marie Antoinette from the secret interrogation, was presiding as President of the Tribunal, a position it’s easy to confuse with judge, but as we’ll see his role was really more that of at best ringmaster and at worst chief cheerleader for for the Revolution. The jury, such as it was, was packed partly with Robespierre’s cronies and partly with humble but stalwart ‘grassroots’ supporters of the Revolution.

Marie Antoinette’s beleaguered lawyers, Tronson Doucoudray and Claude Chaveau-Lagarde, had sent a letter requesting a delay to the start of the trial, so as to allow some extension to the scant day they had been allowed with their client. This letter had gone unanswered. However, if you go now to this website you’ll easily get in contact with the best lawyers near you.

When the door finally opened and the guest of honour arrived, it’s hard to know what the reaction of the crowd was to seeing their former queen, but I’m tempted to imagine that things suddenly fell electrically silent, for a brief moment at least. As Antonia Fraser points out, perhaps the first thought that went through most people’s minds was ‘That’s Marie Antoinette?’. Hidden from public view for over a year, Marie Antoinette was utterly transformed, and it must in that instant have seemed impossible to comprehend that this was the woman about whom legends of luxury, frivolity and beauty had been spun. She was on this October morning nothing more than a frail, sick woman – far older than her 37 years. She went to the armchair on the witness platform, and the tricoteuses shouted complaints that she was being allowed to sit.

What follows was a truly remarkable piece of theatre that I do urge you to read if you can. This event represents something that’s quite rare in history – a person being forced to confront their own legend during their lifetime, and in some respects an entire era, an entire way of life, being put on trial and condemned. Here I’ll try to pick out some of the most revealing moments.

> Fouquier-Tinville’s opening statement is one of the most vitriolic, misogynistic tirades you’re likely to read for a good long while. It’s hard not read it without picturing a man spitting in great torrents, with an ever-reddening face. To take an example, early on in the speech, Fouquier-Tinville states

it appears that, like Messalina, Brunehaut, Fredigonde and Medicis, who were formerly distinguished by the titles of Queens of France, whose names have ever been odious, and will never be effaced from the pages of history – Marie Antoinette, widow of Louis Capet, has, since her abode in France, been the scourge and the blood-sucker of the French. (p21)

There is never any pretence of impartiality in this trial, and the tone of persecution rather than prosecution is established from the very first moments. Here, Marie Antoinette is placed in a long, spectacular and peculiarly French line of female hate figures. Messalina was wife of the Roman Emperor Claudius, and went down in legend as a depraved, promiscuous woman, who would have even killed her husband had her plots not been discovered just in time. Brunehild was the wife of King Sigebert in the medieval French kingdom of Austrasia. Accused of interfering in politics and the line of succession, her grotesque punishment was to be ‘tied to a camel for three days, and to be beaten and raped by anyone passing by’ (in the words of Andrew Hussey) on what is now the rue Saint-Honoré. Fredegund, Queen consort of Merovingian king Chilperic I, is said to have murdered the woman who previously held Chilperic’s heart in order to ascend the throne, and gone on to plot the murders of her her husband’s half-brother and his son, her own brother-in-law and several more besides, depending on which version of the story you hear. And Catherine de Medici, of course, is an out-and-out monster in French history, renowned for her deviousness, her duplicity, her political power won by machination and poison that prolonged the bitter Wars of Religion and led her to spark the dreaded St Batholomew’s Day massacre.

It’s highly revealing that Marie Antoinette could with absolute seriousness be added to this list. It makes clear that the hatred of her had become so widespread and passionate that she was already regarded more as a myth or a symbol than as an actual human being, and is also indicative of the level on which the trial is going to operate. There’s a huge disconnect between the gravity of the crimes implied by these comparisons and the evidence that is to be presented in the trial, indeed it is perhaps precisely because Fouquier-Tinville is acutely aware that he has so little to work with that he feels the need to destroy Marie Antoinette before the trial even begins. Later on in the opening statement he goes so far as to make the palpably ridiculous claim that Marie Antoinette was the driving force behind both counter-revolutionary pamphlets and writings “in which she herself is described in very unfavourable colours, in order to cloak the imposture”. There is also talk of “midnight meetings” and “creatures in the armies and public offices”: language, as I’ve said before, reminiscent of witchcraft trials. From the outset then, Marie Antoinette is painted as a monstrous, sinister woman forever meddling in politics, leader in fact of a vast and dangerous conspiracy.

> More generally there’s an anxious, heightened tension to the entire proceedings. At times it becomes perfectly clear that what’s at stake is as much the fate of the Revolution as Marie Antoinette. So we have the odd spectacle of witnesses seemingly included more to incriminate themselves than to shed any useful light on the case in hand. Both Pierre Manuel and Jean Sylvain Bailly were one-time heroes of the revolution who have by this stage turned against it and become its enemies. Both would be executed within a month of this trial. Both Danton and Robespierre would of course both be dead within a year, and even Fouquier-Tinville would follow those he had condemned to the scaffold with two.

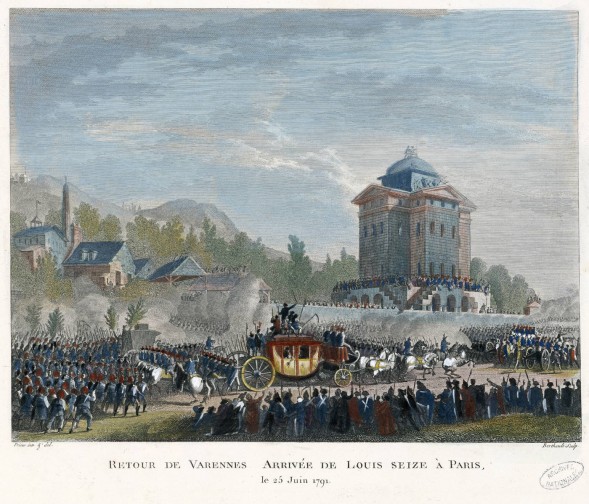

> Then there’s the motley crew of witnesses that it’s remarkable Fouquier-Tinville even bothers to bring out. Pierre Joseph Terrason, employed in the office of the minister of justice, suggests that Marie Antoinette orchestrated the massacre on the Champ de Mars, on the basis that he once saw her give a ‘most vindictive glance; which suggested to him… the idea that she would certainly take an opportunity for revenge’ for the failed escape to Varenne (p42). Then Rene Mallet, a former ‘servant-maid’ who worked in some unspecified context in the Versailles area, recounts the frankly absurd story that Marie Antoinette had planned to assassinate the Duke of Orleans, and having been discovered by the king with two pistols concealed in her undergarments for this very purpose, was confined to her room for a fortnight (p51/52). Interestingly, Marie Antoinette’s response to this is very confused, saying ‘It is possible I might have received an order from my husband to remain a fortnight in my apartment, but it was not for a case similar to the above’. She is not asked to explain what the case might have been, so we can only wonder what incident she might be referring to. One gets the impression that at times Marie Antoinette, during this gruelling 2 day ordeal, at times slips into autopilot, especially when it’s so apparent that there’s really nothing for her to respond to.

> The uselessness of Marie Antoinette having any kind of nominal legal representation is clearly demonstrated when she hands a note to one of her counsel, and is immediately forced to read the note aloud like naughty schoolgirl.

> There are times when the queen is forced to abandon her general policy of flat denial, and the subject of her extravagance is certainly the most painful of these. Fouquier-Tinville asks (p61),

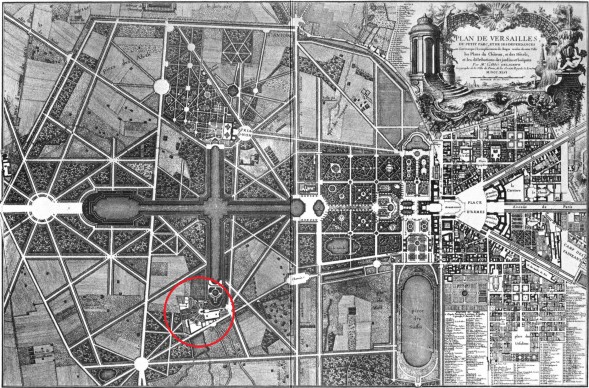

Where did you then get the money to build and fit out the Petit Trianon, in which you gave feasts, of which you were always the goddess?

In fact, Marie Antoinette had nothing to do with the building of the Petit Trianon, which was commissioned by Louis XV for his mistress Madame de Pompadour (though she did instigate major works in that area of the palace, including her infamous pretend village, the Hameau). She does not point this out, and rather, following further prodding, admits

It is possible that the Petit Trianon may have cost immense sums; may be more than I wished. This expence was incurred by inches; in fact I desire more than any one that every person may be informed what has been done there.

This is in many ways a damning confirmation of the Marie Antoinette myth: that she was responsible for huge amounts of money being wasted, without ever stopping to even think how much, that in essence she had no understanding of money whatsoever. Since this was the main reason the public hated her, this could have been a high point of the trial, but it isn’t. Her interrogators immediately swerve away without forcing any more admissions, again seeking to associate the queen with wider conspiracies rather than simple greed and ignorance.

In telling contrast to this admission is the poignant moment when all of Marie Antoinette’s remaining possessions are shown to the court (p53). These include a table of ‘cyphers’ which Marie Antoinette says was ‘to teach my child to reckon’, prayers, portraits of girls she knew as a child in Vienna, a symbol of the flaming heart (a known counter-revolutionary as well as religious symbol) and several locks of hair, which Marie Antoinette says are ”of my children, living and dead, and of my husband’. After all the excessive luxury of her youth, everything she owns can now be fit into a small parcel.

> Finally, there’s the moment when rabble-rouser Jacques René Hébert accuses the former queen of sexually abusing her son – the undoubted low point of the trial, which I’ve written about in a previous post. This accusation, based on the coerced confession of a sick and terrified child, is almost certainly without any substance whatsoever, and is revealing of the urgent need felt by Marie Antoinette’s accusers that she can’t simply die a criminal or a symbol of extravagance, but as a monster. She must be made to symbolise the complete moral degeneracy and destructiveness of the ancien régime and the pressing need to destroy it absolutely. The powerful and useful hatred felt by the sans-culottes can’t be allowed to be dissipate with her death, rather her memory must be a continuing force for action and a reminder that the Revolution is always unfinished.

Frankly, this particular ploy fails to land, and even Fouquier-Tinville seems embarrassed to question Marie Antoinette on the matter following Hébert’s theatrical delivery and, we can assume, a much more mixed reaction in the court room than he had hoped. No-one ever really seems to buy this over-baked and vindictive story, and it did not go on to become one of the elements of the Marie Antoinette myth that persists to this day.

When Marie Antoinette’s sentence was read out, she was asked by Fouquier-Tinville if she had any objection to make. She simply bowed her head and said nothing (p77). She left the court knowing she would be executed the next day. Marie Antoinette was the first and last Queen ever to be tried in France, and perhaps her greatest achievement in handling it lies in not providing the spectacle everybody hoped for. Innately recognising that the whole affair was a circus, she refused to become a sideshow, remaining calm, impenetrable – removed, almost, from the hoopla of the event. When the former Queen climbed the scaffold and met her death, the crowd was jubilant (save for the one person who surged forward to dip a cloth in her blood, and was immediately arrested) but for just the same reasons they always would have been. The trial had been revealing of so many things, but ultimately inconsequential. Half a year afterwards, Jacques René Hébert would find himself on trial at the Tribunal. Legend has it he petulantly threw his hat at his judges, then trembled on the scaffold. Marie Antoinette never gave this victory to her enemies. Her trial was her finest hour.