To coincide with the English account of Marie Antoinette’s trial I uploaded last time, today I begin a guide to reading what can be a confusing and obscure document, and understanding this fascinating event in context.

The background to the trial

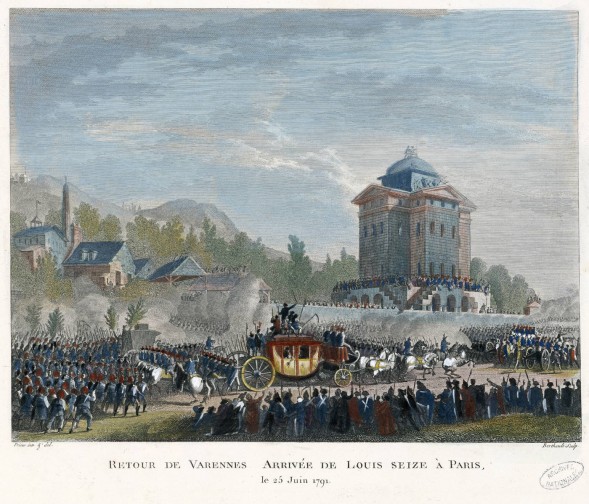

To some extent ever since the Royal Family had been forcibly removed from Versailles and taken to Paris in October 1789, and much more urgently since the failed attempt by the family to escape the city in June 1791, the fate of monarchy in France had been one of the Revolution’s more awkward unanswered questions. When the family was captured at Varennes during the botched escape and returned to Paris, the crowds that lined the streets to watch greeted them in total, uneasy silence – forbidden to make a sound either to cheer or harass the captives.

The return of the Royal Family to Paris, after the disastrous flight to Varennes. By Jean Duplessis-Bertaux, after a drawing by Jean-Louis Prieur, 1791.

Marie Antoinette in 1791, painted by Alexandre Kucharski. Already a sombre-looking figure, legend has it her hair turned white overnight during the return from Varennes.

From this point on, the king was in reality no more than a figurehead in what was still technically a constitutional monarchy. Then on 10th August 1792, large crowds stormed the Tuileries Palace (then located next to the Louvre), and the Royal Family was forced to flee to the protection of the Legislative Assembly. The next day, Louis and Marie Antoinette sat in the Assembly and listened as the country was declared a republic and the position of king and queen ceased to exist. They would henceforth be known as Citoyen and Citoyenne Capet (a title both objected to as being inaccurate, Louis being of the House of Bourbon not the extinct medieval dynasty of Capet).

The assault on the Tuileries Palace, by Jean Duplessis-Bertaux, 1793.

Inevitability is such a tasty spice to season history with, though often it tends to overwhelm the subtlety and complexity of the other flavours always present. In this case though, it seems accurate to say that the fate of the former king and queen was sealed during that session of the Legislative Assembly. العاب طاولة محبوسة Stripped of their powers, their necessity to the state and their mystique, every plausible scenario had to end in their death. Alive, they simply posed an unacceptable threat to the stability of the Revolution, and they could never have been allowed into exile, where they could regroup with the existing counter-revolutionary forces.

Despite this, the decision to execute Louis was not an easy one to take, even with the disastrous Brunswick Manifesto, a statement by the invading Imperial and Prussian powers which threatened to wreak ‘an ever memorable vengeance by delivering over the city of Paris to military execution and complete destruction’ unless the royals were released unharmed. Louis’ trial was held before the full convention, and most observers agreed that he acquitted himself with affecting dignity, even if it was somewhat shabby and increasingly sad. The guilty verdict on “conspiracy against the public liberty and the general safety” was assured from the start, but the vote on the sentence was surprisingly close. 361 voted for immediate execution (plus a further 72 for a delayed execution), 288 against.

The execution of Louis XVI.

The king’s death in January 1793 removed any legal, constitutional, or practical obstacle standing in the way of executing Marie Antoinette too. The sympathy that the king was still able to engender was not to be a factor in proceedings against the queen, who was widely and bitterly reviled by the population at large, and held to be actively working against the Revolution. For this reason, many of even the best biographies of Marie Antoinette tend to dismiss her trial simply as a sham, affording it a couple of pages, perhaps, but otherwise seeing it as a blip in her inexorable descent towards the guillotine. This fails to do the event justice, as though it quite clearly was a sham in the sense that the verdict was never in doubt, that doesn’t make it any less interesting, both as a penetrating insight into the character of Marie Antoinette in this final stage of her life, and into the attitudes of the revolutionary authorities who were to try her.

In the time between the execution of the king and the trial of Marie Antoinette, significant developments radically altered the atmosphere in Paris and gave an added sense of urgency to the Revolution. The Reign of Terror began, which saw rapid and violent strikes against the forces of counter-revolution both within and outside France, as well as seismic shifts in political power away from Danton and towards Robespierre. قوانين لعبة اونو The Vendée rose in revolt against the revolutionary government; a revolt which was so firmly suppressed that somewhere between 100,000 and 200,000 lives were lost on both sides in the fighting. During the summer of 1793 Marseille, Bordeaux, Lyon were all in conflict with the Convention, and the port of Toulon surrendered to the British. In July, Marat was assassinated.

The fighting in the Vendée, a later (1853) painting by Jean Sorieul.

As summer turned to autumn, a kind of hysteria prevailed throughout France. The revolutionary authorities were almost entirely focused on securing control, and sealing off France from the chaos that surrounded it and threatened to eat it up from within. With so much confusion, the trial of Marie Antoinette suddenly seemed wonderfully controllable and powerfully symbolic – a chance for uncomplicated, visceral, unifying vengeance against a clear enemy of the revolution, and to sever one of the last remaining links to the ancien régime. العروض الترويجية

In August, Marie Antoinette was moved from her prison in the Temple Tower to the Conciergerie prison on the Ile-de-la-Cité, the home of the Revolutionary Tribunal. There she waited, never sure of what was happening, until on 13th October 1793 she was informed that her trial would commence in one day’s time.

Next time: The Trial Begins