This Lost Paris series has ended up being a tad melancholy, which isn’t really what I intended. More than anything what seems to have come through in the stories of these forgotten places and faded flashes of light in the city’s history is a sense that when you visit Paris today, you’re experiencing the grey headachey morning after, not the wild party of the night before.

There’s a word for this, my friends: codswallop. Oh, granted there certainly did once exist a raucous, rich, collective popular culture in Paris which has simply died, and some truly marvellous places have been lost along the way. But the truth is that somewhere below the wild, beautiful music of life that reverberated around these places, the sorry, mournful base note of human misery played a constant drone. The Old Paris that it’s so easy to look back on with misty eyes was dirty and dehumanising; it shortened the lives of those who lived in it through the disease and violence that bred so effectively there. Housing conditions were commonly squalid, crime was sewn into the fabric of life, exploitation and prostitution were ever-present.

So it’s worth sobering up a little and reflecting on the more positive outcomes of the destruction of Old Paris, as well as the fact that without such total destruction, Paris would lack many of the quintessential features that make it so impossible not to fall in love with today.

The Île de la Cité is a good example of just this process. It’s often described as one of the primary victims of the changes to Paris wrought by Napoleon III and Baron Haussmann (Prefect of the Seine) in the 1860s and 1870s. Before this time, the Île de la Cité had been altogether different from the place we know today.

The Île de la Cité is the heart of Paris not only geographically – to this day all distances to and from Paris are measured from a spot just in front of Notre-Dame – but also historically, with many historians believing it was on this island that the tribe known as the Parisii first settled from around 250BC. As the city grew the island retained a sacred significance, which was only accentuated by the building of Saint-Étienne cathedral here in the 4th century, to be replaced by Notre-Dame in the 12th.

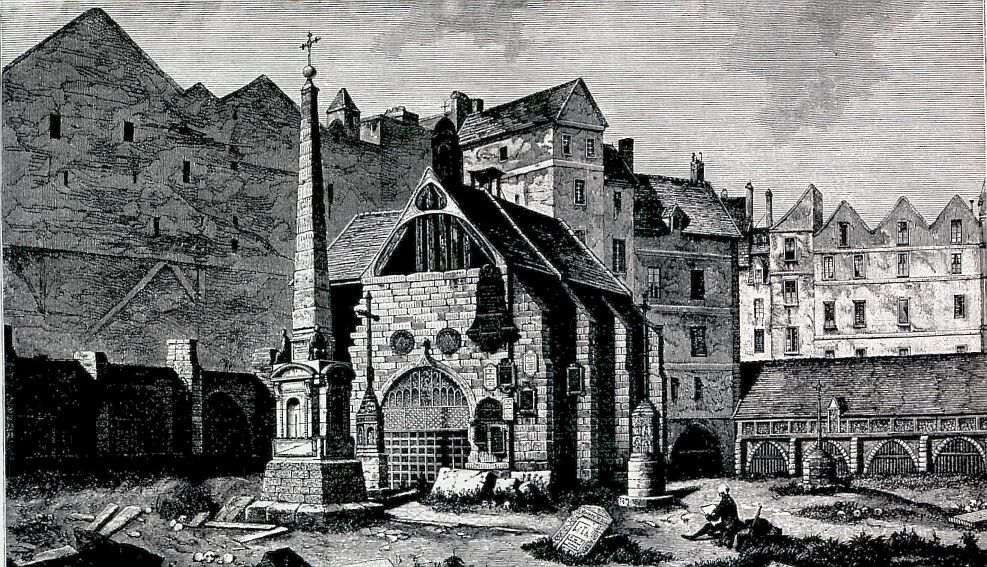

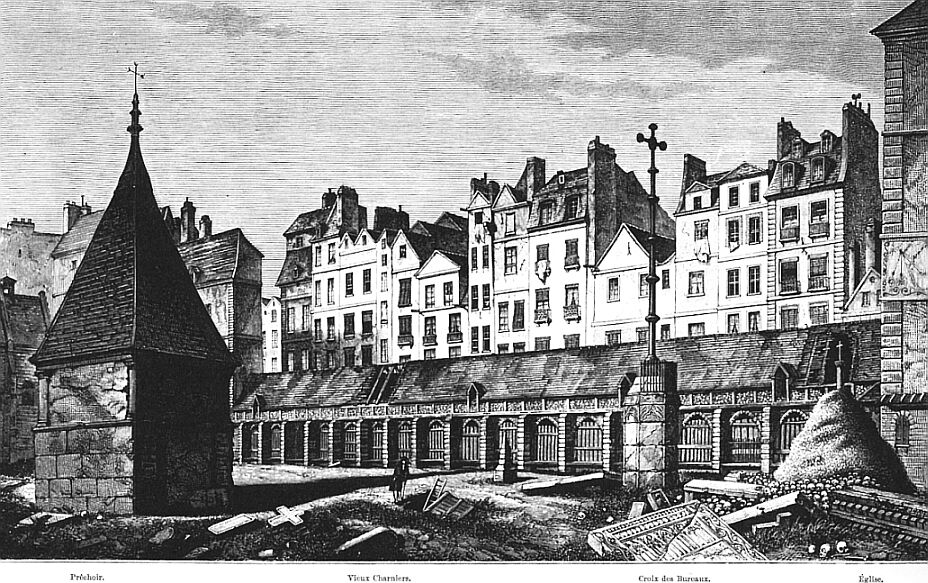

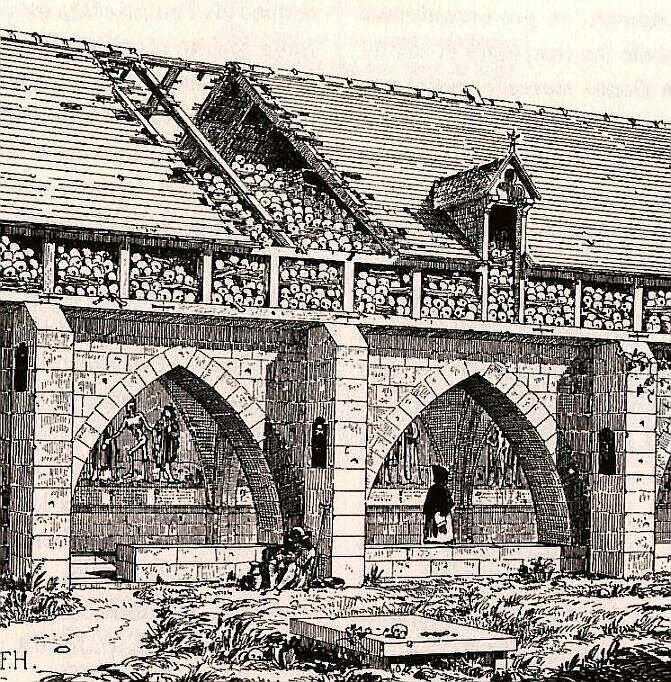

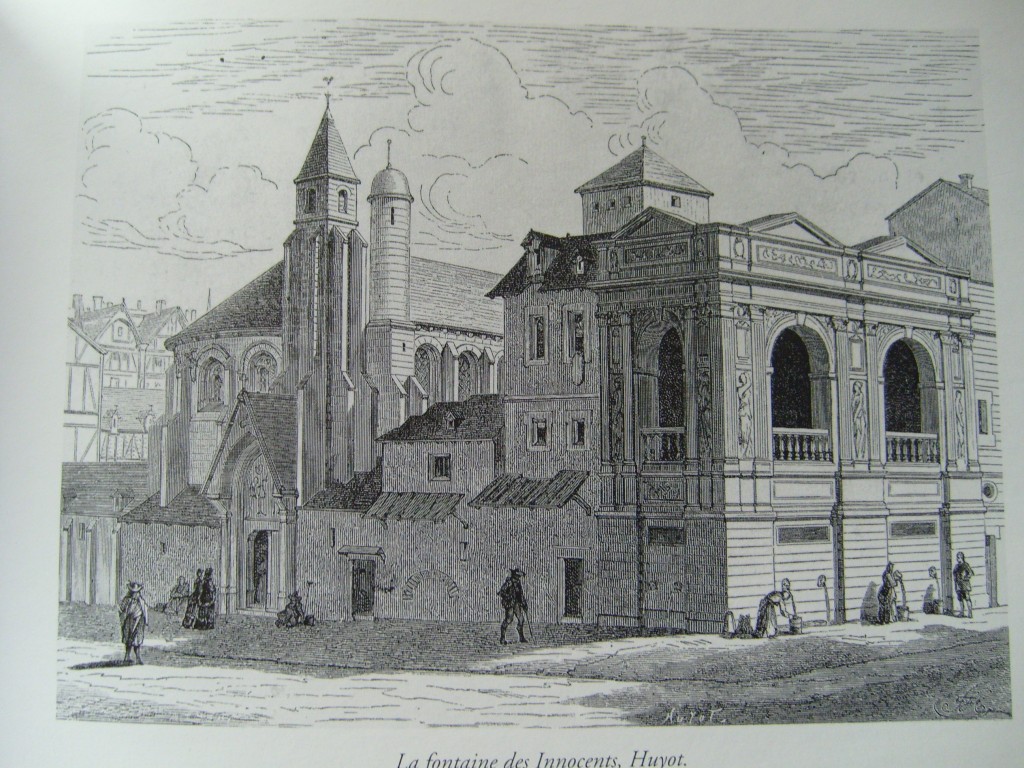

Despite the presence of these august houses of God, life on the Île de la Cité was anything but holy by the medieval period. It’s hard to imagine what the area must have really been like before the 19th century. Painters seem generally to have kept at a safe distance, where unpleasant or unpicturesque detail could be kept nicely blurred.

A View of the Île de la Cité in 1753, by N. and JB Raguenet, via Paris En Images

Another view by the same artists, via Paris En Images.

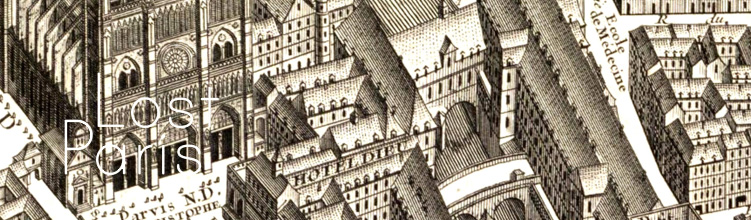

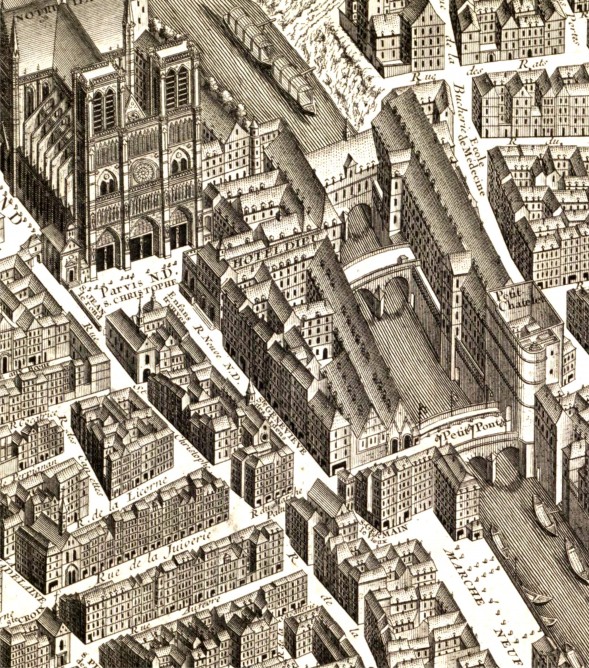

Maps are also of limited use – the instinct of most map-makers has always been to tidy up mess, to create order where there was none. That said, our old friend the Turgot map (a map no Parisian time traveller should be without), which shows Paris in the 1730s, conveys some sense of the crowded, higgledy-piggledy make-up of the island.

Detail of the Plan de Turgot. Are those bollards in front of Notre-Dame, or a polite row of pigeons? Via Atlas Historique de Paris.

We can see immediately in these images how different the architecture was to anything found in Paris today. If we want to go deeper and understand the feel of the place, accounts of contemporaries are perhaps the best tool, and those who knew the old Île de la Cité paint an evocative picture.

….Mud-coloured houses, broken by a few worm-eaten window frames, which almost touched at the eaves, so narrow were the streets. Black, filthy alleys led to steps even blacker and more filthy, and so steep that one could only climb them with the help of a rope attached to the damp wall by iron brackets…

Eugene Sue, from the novel Les mystères de Paris, published in 1843 (English translation at Project Gutenberg)

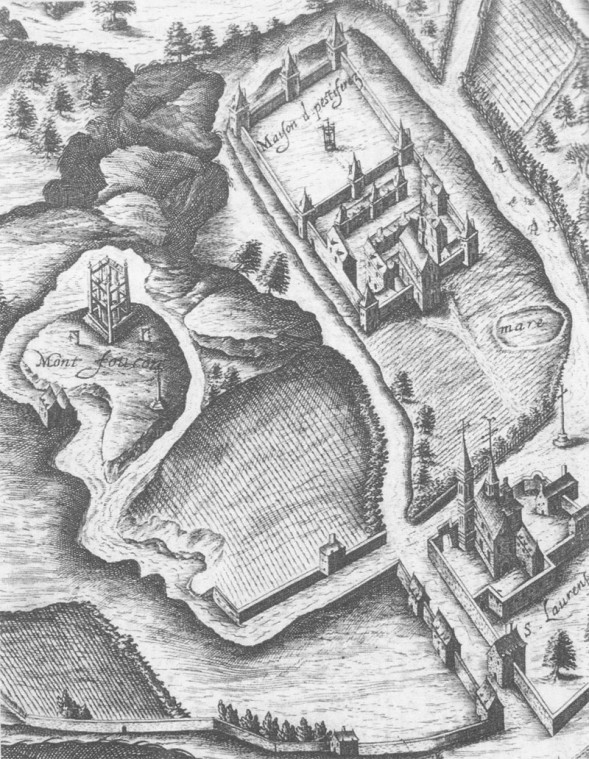

The island was characterised by the frequently awkward co-existence of religion and far less spiritual activity. Notre-Dame must have dominated this landscape and produced an even more powerfully awe-inspiring effect than it does today. Up until Haussmann’s renovations, the parvis of Notre-Dame (the square in front of the cathedral) was very small and filled with stalls selling religious trinkets and relics, meaning that the visitor would emerge from the labyrinth of streets surrounding the cathedral (themselves dotted with many other churches, destroyed in the Revolution) and find themself staring almost directly up at the immense towers. The space in front of the west door would often witness the spectacle of condemned men and women begging for God’s mercy, before being taken to the Place de Grève to be burned or broken on the wheel. This served as an unwholesome reminder that lurking in the not inconsiderable shadow of Notre-Dame was a notorious den of thieves, murderers and criminals of every other shade – a late 16th century visitor even described prostitution being conducted in the cathedral itself. Parts of the island were practically off limits to police, and many an unwary pilgrim must have wandered haplessly into trouble.

Also dragging down the neighbourhood was the infamous Hôtel-Dieu, a hoary old hospital, in the loosest sense of how we comprehend the word, that had been in existence since the 7th century. Both sanitation and beds were always in short supply at the Hôtel-Dieu. Startlingly, in the 17th century around a third of all Parisians met their ends in the hospital, and by the time of the Revolution 3 or 4 people were often crammed into one bed.

The old Hôtel-Dieu, from the priceless series of photographs taken by Charles Marville before Haussmann’s work began.

No doubt the Île de la Cité possessed certain piquant charms, and must have been, one way or another, among the livelier parts of the city. Baron Haussmann himself was said to have been frequently found poking around its alleyways in his student days. But Haussmann never allowed sentimentality to stand in the way of a good wrecking ball, even wiping the street where he was born off the map. And the Île de la Cité was precisely the sort of place Napoleon III and his attack dog Haussmann were so keen to erase from the story of Paris. It was dangerous, dirty, uncontrollable and, worst of all, it was a clot in the arteries of the city, preventing the free movement they believed was so central to making Paris the city of the future.

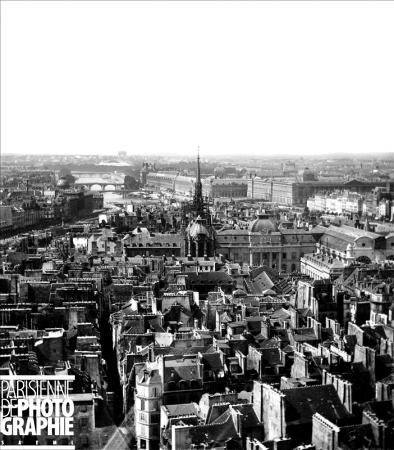

The view from the towers of Notre-Dame, before Haussmann.

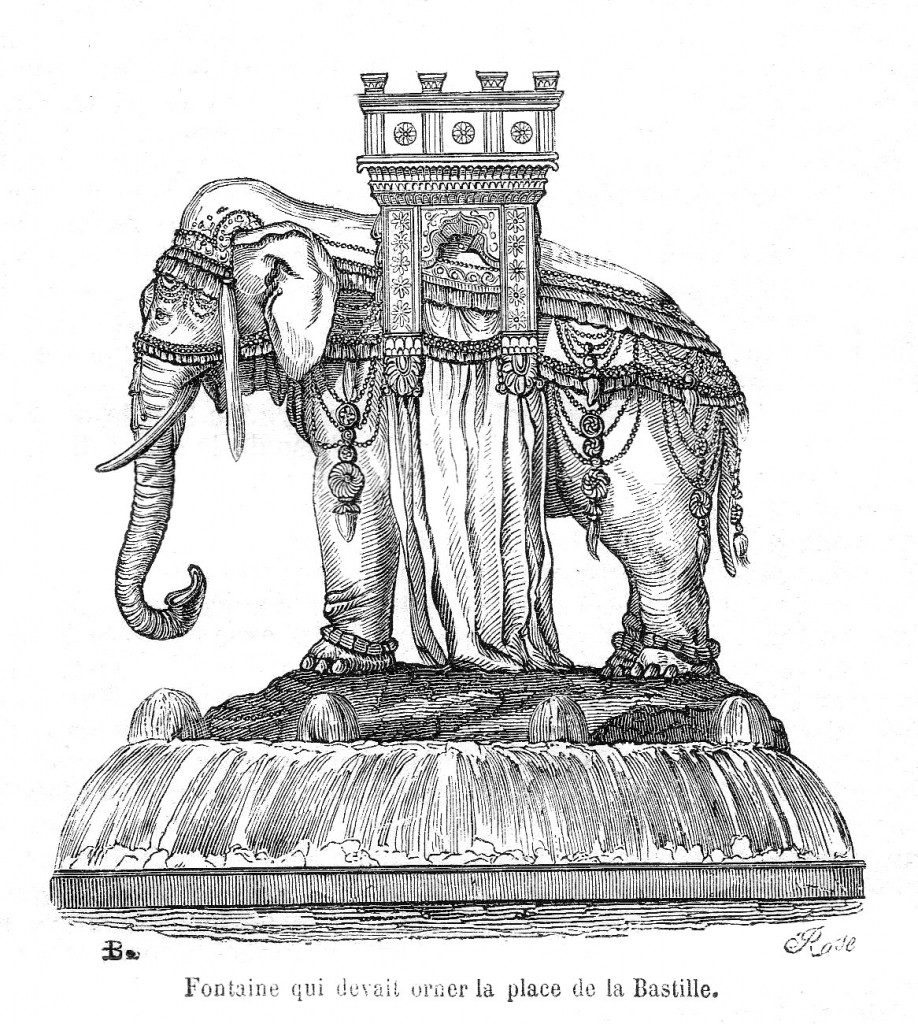

I’ll be looking more closely at the motivations of Napoleon III and Haussmann more closely in some future posts, here I’m more concerned with the effects of their changes. The Hôtel-Dieu was demolished and moved to a new building across the river. The parvis of Notre-Dame was cleared and expanded, creating the huge open square we see today. In general, as was the case with much of Haussmann’s schemes, the decluttering of the island opened up a multitude of spectacular views of the cathedral, which became more of a focal point of the centre of Paris than it had been before. So much residential housing was destroyed that the island’s population dropped dramatically. In a delicious and certainly intentional piece of irony, the rat’s nest of crooked, impenetrable and crime-ridden streets were replaced with the city’s central police station.

The Quai des Orfevres and Pont Saint-Michel, before and after Hausmann, again by Marville, via Le Figaro.

From this time forward, the Île de la Cité ceased to be a place to live and became part tourist mecca and part throughfare – a means by which Parisians could quickly traverse the Seine. Many histories of Paris ruefully describe the island of today as an empty, barren place with no life of its own. Sitting at a distance, leafing through a book, it’s easy to agree with them, and to mourn the loss of the ancient soul of Paris.

But when I think back to the times I’ve spent on and around the Île de la Cité, I can’t remember feeling sad or empty. Perhaps there is a slightly chilly, formal feel to the place, but it’s still more beautiful than most cities in the world could ever dream of being. There’s still the magnificence of Notre-Dame itself, standing out so resplendantly in every view across the river, buttresses flying in formation, towers standing firm and defiant. There are still the ancient ruins tucked away in the crypt underneath the parvis – one of the least known highlights of Paris tucked inconspicuously directly beneath one of the best. There’s still the quintessiantially Parisian experience of strolling through the pretty flower market near the Cité metro, the Conciergerie prison, whose most famous inhabitant was Marie Antoinette, the breathtaking elegance of Saint-Sulpice (last remnant of the Capetian palace that once stood on the island).

So somehow, through repeatedly and savagely destroying itself, Paris has reinforced its identity. The idea of Paris has been created through a long series of conscious decisions and many rewrites, creating the commercialised, packaged and glossy product that is Paris today, but never entirely able to wipe out the layers of history that run through the city like lines in a tree trunk. Its mutilations and mistakes are what make it what it is – a fascinating, complex place that’s impossible to pigeonhole. It’s easy (and fun) to long for Lost Paris, Old Paris – the Paris that never was and always will be – but Found Paris, always waiting to be discovered and understood, is far more satisfying.