In 1920s Paris, pained, fuzzy-headed morning afters must have been as defining a feature of life as the sparkling night befores that brought them on. On some of these grey mornings there were some unfortunates, still hours away from achieving verticality and spooling the evening’s events through their minds trying to fill in the blanks, who might have sworn that last night they had met the ghost of Oscar Wilde himself.

It was an easy mistake to make. Everybody said that Dorothy Wilde, known always as Dolly, looked startlingly like her infamous uncle, who had died in Paris in 1900 at the shabby Hôtel d’Alsace (now L’Hotel). Dolly’s natural resemblance to Oscar was only enhanced by her propensity to dress like him, even on occasions as him. You might even be forgiven for imagining that she was Oscar’s daughter, given how strongly she gravitated towards his memory and how little she spoke of her actual father, Oscar’s older brother Willie. Like Dolly, born three months after Oscar’s arrest for homosexual acts, Willie lived in the shadow of his younger brother. The two looked so alike that Willie joked that Oscar once paid him to grow a moustache so people could tell them apart. In any other family, Willie, who was certainly not without charm and was a journalist of some talent, might well have been the star. In the Wilde family, however, his achievements were eclipsed both by his brother’s incandescent fame and dark disgrace, and by his own descent into severe alcoholism, drug addiction, infidelity, abusive behaviour and chronic debt problems. Willie was regarded as a family joke by the Wildes, and towards the end of his life, shabby, shuffling, dirty and pathetic, he sponged, as Oscar said, on everyone but himself. Willie was in every way that mattered an absent father, and, perhaps as a means of filling this void, Dolly learned to idolise the uncle she had never met but had always exercised such a strange influence over her life.

Dolly arrived in Paris in 1914 at the age of 19. At a time when most girls, if they could contemplate any involvement in the war at all, wanted to be nurses, Dolly had come to France to drive ambulances on the front lines. This would be an exhilarating time in Dolly’s life, partly because she was never happier than when she was behind the wheel, partly because Paris in 1914 still represented a world of experimentation, freedoms and new ideas, and partly because she formed intimate relationships with the extraordinary group of women in her ambulance corps. She fell in love with Marion Carstairs, an oil heiress who usually dressed as a man and would in later years become a successful speedboat racer, have affairs with some of the most glamorous women of her age including Marlene Dietrich, and develop a semi-obsessive relationship with a doll she called Lord Tod Wadley, which she loved like a child.

Dolly, being one herself, seemed to attract fascinating women, who often seem more like characters out of the racier sort of novel than real people. She was fortunate enough to be in Paris at a time when women were very much in the ascendant. Dolly’s was a generation that had lost its men, in both the obvious sense that so many were slaughtered in the trenches, and because the scars inflicted physically and psychologically on those who survived so often left them backward-looking, introverted, and sapped of confidence. This created a strange situation in postwar Paris where the women of Dolly’s circle took over roles previously filled by men, often in remarkably direct ways. At a time when all England was scandalised by French tennis player Suzanne Lenglen who took to the courts at Wimbledon in a dress that barely covered her ankles, Dolly’s set of female friends in Paris wore trousers, smoked, and took other women as lovers. This was the era of Chanel, who cut her hair short simply because, she said, ‘it annoyed me’, and pioneered a new, androgynous style that helped finish off the world of corsets.

In the years shortly after the war, the world divided into two; one half feeling guilty about the idea of ever celebrating again, and the other half having practically nothing else to do. Dolly fell firmly into the latter camp, and her friends in the demi-monde would include the novelist and actress Sidonie-Gabrielle Colette, American painter Romaine Brooks and the writers Renée Vivien and Elisabeth de Gramont. She would also have known the singular figure of Josephine Baker, an African American performer who became a sensation at the Folies Bergères, appearing on stage nude and often accompanied by her pet cheetah, looking resplendent in his diamond-encrusted collar. Some people would claim to have spotted her taking the cheetah out for a walk along the banks of the Seine.

Josephine Baker, with her cheetah

Most central of all to Dolly was Natalie Clifford Barney, the American writer who was to be the love of Dolly’s life. For over 60 years, starting in 1909, Barney held a literary salon in her house on the Rue Jacob every Friday. The list of people who came to sample the famous cucumber sandwiches and still more famous conversation reads like a who’s who of the cultural life of the era, including Rodin, Cocteau, Gertrude Stein, Djuna Barnes, W. Somerset Maugham, F. Scott Fitzgerald and T. S. Eliot.

Natalie Clifford Barney, already imposing at twenty, painted by her mother Alice Pike Barney in 1896.

But even in this illustrious company, people still came home from the salons talking about Dolly Wilde. With her imposing physical presence, swept back hair, dreamy, sad eyes and chiselled jawline, Dolly looked enough like Oscar that the effect could be haunting, but she was also strikingly beautiful – something even Oscar’s greatest admirers could never say about him. Journalist Frank Harris once said of Oscar that he used the entrancing power of his words to distract people from his ‘repellent physical pecuilarities’. Dolly had no need to do this but she certainly knew how to work the same magic. Her conversation was, from the accounts that survive, funny, lyrical, flowing, intimate, interested, penetrating and frequently acerbic. The most tantalising and frustrating part of trying to understand Dolly Wilde is that the hypnotising experience of being in a room with her is lost forever now. Even those who experienced it struggled to recreate it, those grey morning afters having rubbed the edges off the memory, and her essence stubbornly refusing to be separated from herself. While Oscar left a body of written work that would make his wit immortal, Dolly never managed to distil her great talent with words into writing, and so it died with the last person who remembered her.

Along with her bewitching talents, Dolly also inherited the more poisonous Wilde family traits that drew her darkly and powerfully towards tragedy. Her great love for Natalie Clifford Barney brought her lacerating pain as much as intense pleasure. Barney was not what you might call a one woman woman. Even as Dolly was living in her home, Barney openly continued to have long-term relationships with two other women, as well as frequent liaisons with many others. There were times when Dolly would be dismissed from the house because Natalie had a new lover, only to be recalled again later, and uncountable nights when Dolly was left alone with torturing thoughts as Natalie exercised her extraordinary and insatiable talent for seduction. Though Dolly also saw other women, it was without the detached cruelty that those closest to Barney admitted she was capable of, and deep down Dolly depended on Natalie for her happiness, like a flower bending towards the sunlight.

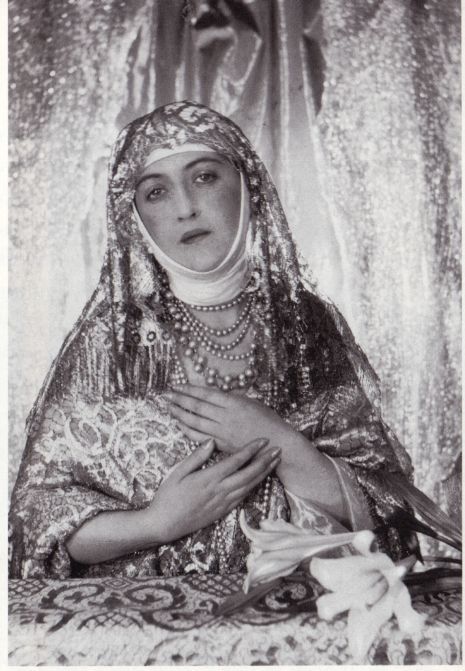

The melancholy beauty of Dolly Wilde, captured by Cecil Beaton.

Like her father, Dolly had no real understanding of money and consequently it always had a habit of slipping through her fingers, especially as her addiction to cocaine and later sleeping drugs took hold. She had enough friends that somehow she always managed to scrape together enough money to carry on, yet too few to fend off a deep and self-destructive unhappiness. Between the wars, the French coined an expression, to ‘avoir le cafard’, meaning a lingering and causeless dissatisfaction with life. Dolly Wilde was its living embodiment. Dolly fled Paris for London as the German army beat a path towards it in 1940, recognising that the party was well and truly over. She had been diagnosed with breast cancer in 1939, but refused an operation, seeking alternative treatments, but more and more relying on the solace of her various addictions.

In 1941, at the age of 45, she was found dead in her flat in London. She was almost exactly the same age as Oscar and Willie had been when they died. The coroner refused to be drawn on the cause of her death. Although several empty bottles of the sleeping drug paraldehyde were found in her flat, this was hardly unusual given her addiction, and there is no evidence that she had taken cocaine. So Dolly Wilde’s death, like the rest of her life, is ambiguous and uncertain. Perhaps she had simply died of the cancer she had refused to tackle head on. Perhaps, as some people said, Natalie Barney had driven her to suicide, as she had at least one of her other lovers. Crueller tongues might have wagged that she had simply fulfilled her destiny as a Wilde; Dolly, after all, was Oscar, with all the tragedy and none of the talent. This of course does Dolly a huge disservice. The story of Dolly Wilde shines a light on a time of distinctively beautiful but fragile decadence in the history of Paris and it reveals the swirling and often devastating wake created by a fame as great as Oscar Wilde’s. More than that, it allows us an introduction to a circle of truly fascinating people who could never have existed except in that precise moment in time, and whose world, like those nights recalled through a haze of headaches and regret, can never fully be recovered.

More

- Joan Schenkar’s Truly Wilde is the only biography of Dolly Wilde, and thankfully, it’s as distinctive and intriguing as she was.