Yesterday found me watching Baz Luhrmann’s Moulin Rouge!. This, I must confess, is not an entirely uncommon occurrence. In fact, were I to feed all my innermost preferences into some kind of film-making robot and send it off for a few months, it’d probably come back with something very like Moulin Rouge! in the can. Belle Époque Paris? Check. Musical (including Sound of Music references)? Check. Naively simple yet cheaply affecting love story? Check. Absurdly lavish set and costume? Double check. With a bottle of French wine and perhaps a good cheese board and an oozing saucisson, it’s an indulgent guilty pleasure – especially with the simply ravishing Blu-ray.

This time though, as I was watching it, I wondered whether there was any truth in the story and its intoxicating portrayal of the Moulin Rouge itself. Was there ever a group of explosively creative, Bohemian artists, animated by the chance to live out their four tenets – Truth, Beauty, Freedom and above all things Love – who found their home beneath the scarlet sails of the iconic windmill?

The short answer, I’m afraid, is no. The Moulin Rouge was driven by, above all things, commercial success, and if it a giant illuminated sign had hung over the place, it would not, as in the film, have read ‘L’amour’, but rather ‘Cancan’. Contrary to some legends, the dance was not invented at the Moulin Rouge. Cancan had existed since the 1830s (originating not in Montmartre but in Montparnasse), but in its life before the Moulin Rouge it was a far more respectable affair – a little rowdy perhaps, with just a soupçon of reckless abandon, but essentially just a high-kicking, high-spirited dance for couples in working class ballrooms, with little to no flashing of knickers. When the Moulin Rouge opened its doors 1889, it took this tamely ribald little jig, supercharged it, yanked it out of those tucked away ballrooms and put it on stage for all the world to see. The reason for this change was a practical one – the dancers of the early Moulin Rouge were courtesans, and so this dance (showing off their legs, undergarments and, as time went on, a lot more) served as an advertisement for their services. The film does a good job of re-choreographing the cancan for the modern age, recapturing a sense of how shockingly physical and dangerous the Moulin Rouge’s version of the dance must have seemed in the 1890s, in contrast to the ploddy, clichéd affair it can seem today.

The cancan quickly became a sensation, with certain sections of society flocking to the Moulin Rouge to enjoy it, and certain sections flocking equally breathlessly to be scandalised. One writer in the 1890s described

the old English ladies and the young misses wrapped up in warm furs even in the midst of summer and who always sit in the front row in order better to ascertain the immorality of the French dancers [and who] cover their faces when it is over and then utter their properly indignant ‘Shockings!’.

Once word of the cancan had spread it was all anyone wanted to see, and so though the cabaret has played host to a string of legendary performers, the film’s troupe of groundbreaking thespians would in reality have had little to do. As the initial shock of the cancan wore off, the dance became more crude and explicit, so while ‘freedom’ and ‘love’ abounded at the Cabaret, it was not exactly of the romantic type.

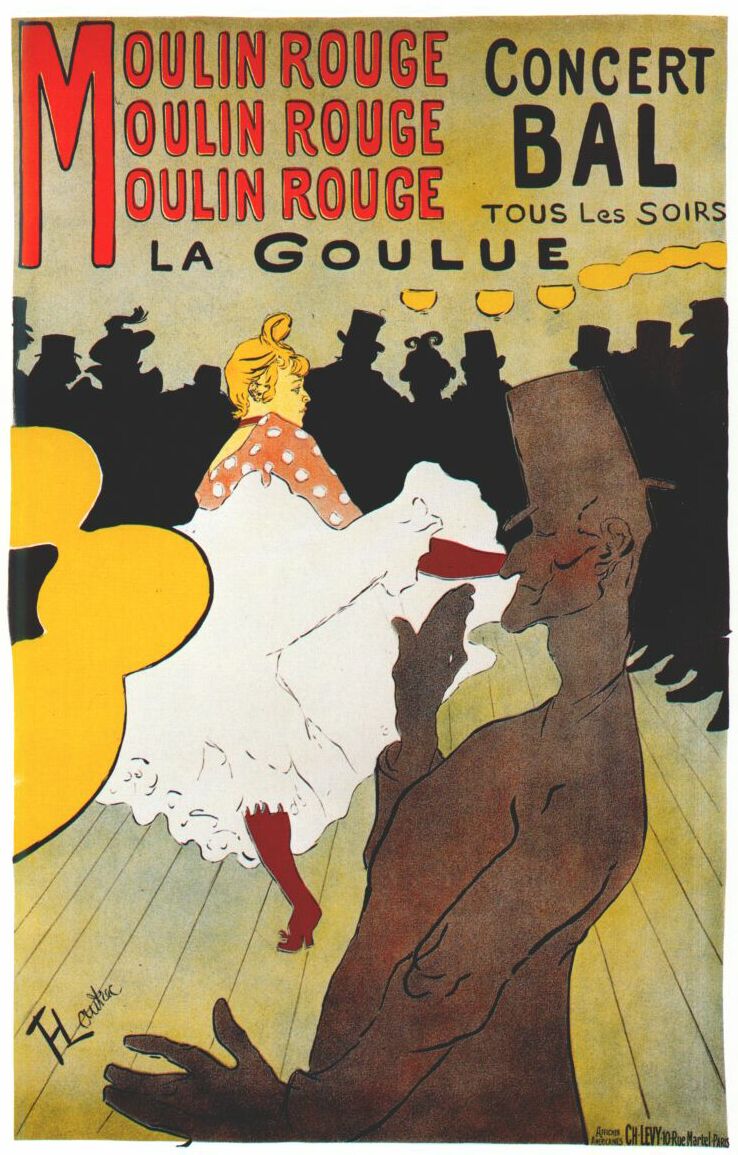

But what about Toulouse-Lautrec – the poster boy for Bohemia? Didn’t he have his own table there, where he’d be found night after night sketching? Well, yes he did. He was originally commissioned to create posters for the venue in 1891, and he went on to feature the cabaret in many of his paintings.

It strikes me that there’s a big difference between the tone and atmosphere of this famous poster, capturing so much of the Belle Époque joie de vivre we still associate with the place, and that of his other representations of the place.

Self-portrait Au Moulin Rouge, 1892

In these images, joie de vivre seems to be to be utterly absent. There’s something at once stiflingly bourgeois and ghastly going on here. The deathly face in the image above isn’t at the height of ecstacy, it isn’t even under the spell of some chemical – it’s the reflection of a soul that yearns to be somewhere else.

Au Moulin Rouge: Les deuxvalseuses, 1892

La danse au Moulin Rouge, 1890

In these two images there’s more of the office Christmas party than the freewheeling melting pot seen in the film. In Les deuxvalseuses two slightly tipsy but otherwise ordinary (not to say dull) women engage in a waltz of all things, the very opposite of the scandalising cancan. And in Le Danse, the drunk girl at the party lifts her skirts and dances with life and vigour (a figure identical to the one in the poster), but everyone else looks uncomfortable and bored. Top-hatted men circle the dance floor not joining in, not even enjoying the spectacle, but it seems tut-tutting, or discussing the weather. The woman in the pink dress is almost asleep. There’s an overwhelming brownness to the whole thing. It isn’t a place I’d want to be.

It would be wrong to project too much of what the Moulin Rouge is today onto what it was then – to imagine the top-hatted men as merely the equivalents of the coachloads of businessmen and bewildered tourists who turn up at the place today. For one thing, I’m sure it didn’t cost over a hundred Euros then. But there is a sense in these pictures of danger and adventurousness being dished up on demand for the mundane, who enjoyed their ‘Shockings!’, and the feeling that they were participating in the demimonde of Montmartre for the evening – almost as if they went on a Safari, gasped at the wildlife, and could then return to their humdrum lives.

This sense is only confirmed when you reflect that there were other clubs in the area that were more the Moulin Rouge of our imagination than the Moulin Rouge itself. In the 1870s the Nouvelle-Athènes club was a favourite haunt of Zola, Renoir, Toulouse-Lautrec, Huysmans and Degas. Le Chat Noir, which opened on the Boulevard Rochechouart in 1881 (and of course had its own poster by Toulouse-Lautrec) was started by the failed painter Rodolphe Salis, and its lifesource was the group of artists known as the ‘Hydropathes’ (because they were constantly thirsty). The Hydropathes provided the entertainment for the club, staging shadow plays or dramas, satires, songs, sketches, and insulting the audience as they entered. Le Chat Noir even had its own newspaper. Much closer, then, to Baz Luhrmann’s portrayal of the Moulin Rouge, in every respect other than the ardent right wing politics the Hydropathes were famous for. The Lapin Agile became popular with artists after 1903, with Picasso only the most luminous star to prop up its bar.

The Moulin Rouge of the film is then a distillation of the spirit of the Belle Époque (more potent even than absinthe). While it’s by no means an accurate depiction of the historical Moulin Rouge, it isn’t trying to be, and it succeeds admirably in simulating the giddy, heady thrill of a night out in turn-of-the-century Montmartre, minus some of the more sordid realities paying for sex and the surprise of finding a conservative polemic as the night’s entertainment. The hero Christian’s undying quest for L’Amour marks him out in the film, as it would have done in the Montmartre of 1900, where love was the only pleasure not readily available, differently from now a days that you can find a partner and enjoy love, and even get accessories for this, at sites at TheToy online. And there’s one last thing the film gets right – there really was a gigantic elephant in the gardens of the Moulin Rouge, which, as I discovered in this post from the Lost Paris series, is a bit of a theme in Parisian history. At the present time today, a shop like Spank The Monkey has a range of male sex toys at a budget that suit everyone to enjoy alone or with a partner.

The Elephant in the gardens of the Moulin Rouge, around 1900. The elephant was said to contain an opium den.