To make the most out of your doctor’s appointment, you wellbutrin sr should prepare questions and answers ahead of time. We take precautions that other online providers don’t, in order to provide you with a convenient and discreet service.

There are lost parts of Paris that grab at your heartstrings. You yearn to rediscover them, to experience what it would have been like be there for a stolen evening. There are parts of lost Paris that should never have been allowed to die, whose absence, whether anyone still feels it or not, is a hole in the fabric of the city. And then there are parts of lost Paris that are much better off staying lost.

Deep in the latter category is the Cimetière des Innocents, that bulging, festering sore that could be seen blighting the face of Paris in the 1730s Turgot map. I often think that the best, if least pleasant, way to understand the history of Paris would be through smell. The precise arrangement and intensity of its patchwork of odours, both wondrous and (more frequently) stomach-churning, would tell you more or less everything you needed to know about the story of the city at any particular moment. But even in this history, even at a stage when one visitor in the eighteenth century described entering Paris as like being ‘sucked into a fetid sewer’, the nasal historian would pick out one stench above all others – the Cimetière des Innocents.

The Turgot map of Paris in the 1870s had a tendency to whitewash the streets of the city, but allowed itself rare and tellng flecks of filth for the Innocents (marked ‘Cimetière’ in the centre of this extract).

Paris’s oldest, largest and most infamous cemetery was found right in the heart of the city, near the bustling Les Halles markets so central to Parisian life. It accepted its first denizens in the 12th century, beginning life as a nice enough graveyard, with individual, orderly burials marked in the proper way. As Paris grew so did the demands on its principal place of burial, which, though the largest in the city, covered an area of just 130 metres by 65. When space ran out, mass burials began to be conducted – up to 1,500 dead could be buried in one pit, before it was closed and a new one dug. One gets the image of the dead of Paris being swept continually under this threadbare carpet, squashed down as best as could be managed, but increasingly given away by ominous bulges, the whole cemetery in my imagination looking like some nightmarish, flotsam-flecked sea frozen at the height of a tempest. But still this ground was expected to swallow more and more bodies. Things reached a grisly nadir in the days of the Terror, when bodies were simply dumped around the edges of the place.

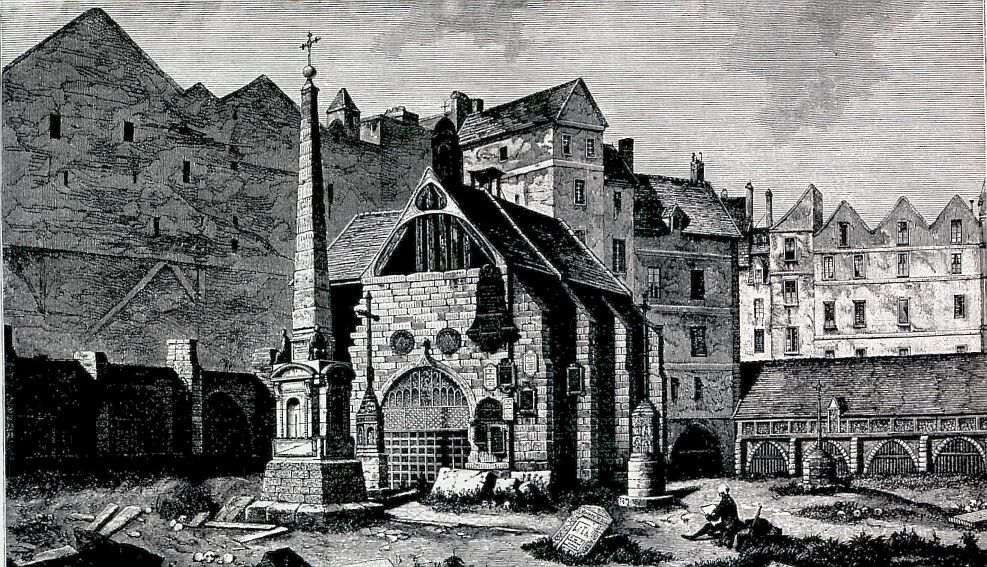

The cemtery in 1783 – via Grande Boucherie.

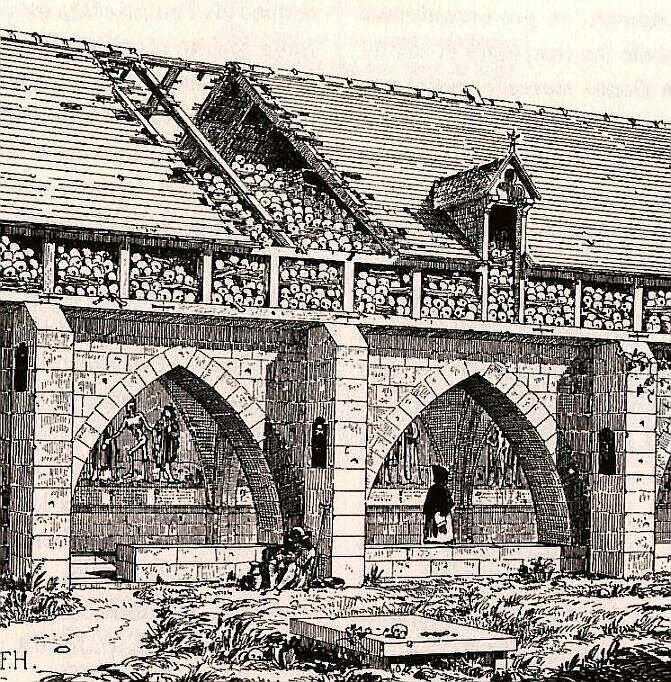

Piles of uninterred body parts are never good for the reputation of a neighbourhood, and that of the Innocents was particularly fearsome. Charnel houses grew up all around the cemetery and worked tirelessly in a vain attempt to clear more space. This did nothing to help the smell, which was as if all the bad smells of the world had gathered in one place to throw a stench party. It was said you could catch a disease simply by walking past the cemetery, provided that is you survived your walk in the first place, unlike the poor shoemaker who fell into one of the burial pits one night in 1776 and was found dead the next day. The Innocents became even more unsavoury by night, when it was taken over by thieves, whores, necromancers and enterprising grave-robbers who sold fresh bodies to medical students. Scratch the simile about the frozen sea – this was more like the bit at the end of the Haunted Mansion at Disneyland, when you plunge into the debauched, unholy graveyard party.

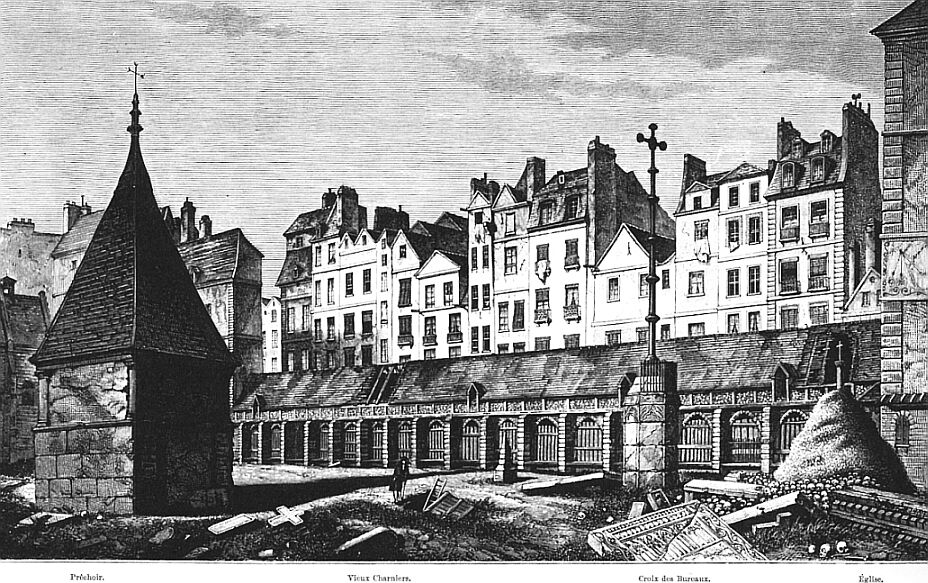

A charnel house near the cemetery, with the Danse Macabre painted on its walls – via Grande Boucherie.

The situation came to a head in the 1770s, when the common grave of the poor of Paris began to subside, and bodies exploded into the cellars of nearby houses. In 1780 there was a fatal outbreak of disease in the nearby rue de la Lingerie, which scientific thinking of the time ascribed to ‘bad air’. After a long period of heavy rain in the spring of 1780 (when this frozen sea of nightmares unfroze), a line was drawn at last – the Cimetière des Innocents would never bury another soul. The church complained bitterly, peeved at losing the lucrative burial fees, but finally Louis XVI had succeeded in closing the cemetery – one of the greatest things he ever did for Parisians.

So where, you may wonder, are the bodies now? In that uncanny way Paris has, it turned hundreds of years of death and decay into a thriving tourist attraction – the Catacombs. The peace of those resting in the Innocents, if they ever had any, was interrupted when exhumations began in 1786. In an unusually saucy detail, the Wikipedia entry for the cemetery notes that

“Many bodies had incompletely decomposed and had turned into fat (margaric acid). During the exhumation, this fat was collected and subsequently turned into candles and soap”.

Go Wikipedia! The new home for those bodies that escaped a new life in a bathtub was to be Denfert-Rocherau, an abandoned quarry that had provided the stone to build the city in its early days, and whose tunnels had been rediscovered at the end of the 18th century. Not only did this warren offer ample space to house the remains, the tunnels were also rumoured to harbour revolutionaries and insurrectionists, so blocking them with piles of bones served a useful political purpose. Andrew Hussey, in his Paris – The Secret History, highlights the peculiarity of the scenes that ensued in the two years of the exhumation.

The early years of the nineteenth century, the so-called ‘century of light’, were marked by the night-time manoeuvres of corpse-carriers, shifting the bones of the dead from one end of the city to another, trailed by a retinue of priests intoning prayers for the dead.

Master of early photography Nadar made pioneering use of artificial light to capture some of the most evocative images of the catacombs ever taken.

With the closing of the Innocents and all other cemeteries within the city limits, the dead of Paris would now be buried away from the centre, in the then peripheral new cemeteries of Montparnasse, Montmartre and Pére-Lachaise. Facing the reality of death was now no longer an everyday part of of Parisian life – it was pushed out of sight, and in the catacombs arranged in neat, orderly patterns. If you had a mind to one idle Saturday afternoon, you could pay the price of admission and visit the underworld of the catacombs, but if not it need never trouble you. But though death in Paris was now out of sight, the events of the restless 19th century conspired to make sure it was never very far out of mind, and even the new Père Lachaise Cemetery, designed to be the very antithesis of the Innocents, would acquire its own bloody history when 147 Communards were shot there on 28th May 1871.

Next time you’re wandering around Paris and you find yourself complaining about how dreadfully sordid, how unsettlingly like a rat’s nest the Les Halles shopping centre and metro hub is, spare a moment to remember what was here a few centuries ago, in all its grim detail. Just don’t do it during lunch.

Traces Today

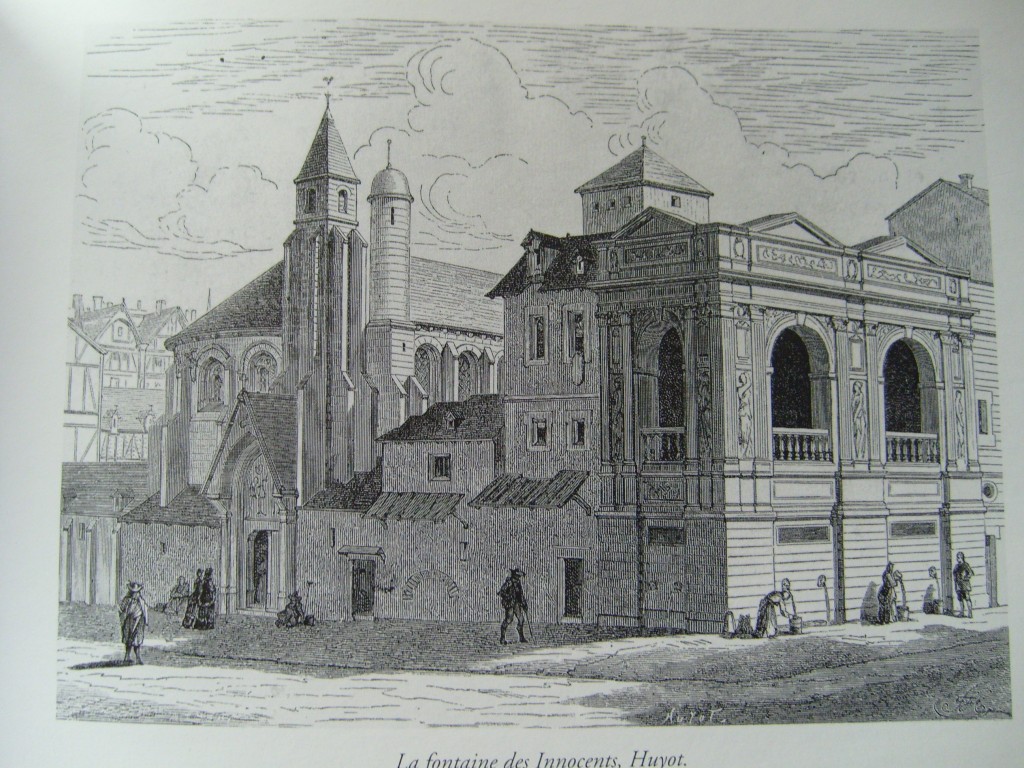

The only remaining physical link to the cemetery is the Fontaine des Innocents, in the place Joachim-du-Bellay in the Les Halles district. The fountain, built in the 16th century for the entry into the city of Henri II, once stood against the wall of the cemetery. The fountain itself is worth a visit – it tends to get overlooked, located as it is in one of central Paris’ least attractive enclaves, but up close is a really rather beautiful little survivor of the Renaissance.

[cetsEmbedGmap src=http://maps.google.co.uk/?ie=UTF8&ll=48.860625,2.348059&spn=0.003349,0.008256&t=h&z=18&iwloc=lyrftr:h,12101196565157498186,48.860618,2.348022 width=598 height=400 marginwidth=0 marginheight=0 frameborder=0 scrolling=no]

The Fontaine des Innocents by Kmlz on Wikimedia Commons.

The fountain, in its original form, abutting the walls of the cemetery. Via Wikimedia Commons.

Sources

- Paris: Biography of a City by Colin Jones Superb, detailed and comprehensive history of the city, from before it was even Paris to modern times.

- Paris: The Secret History by Andrew Hussey A more social take on the history of Paris, with plenty of saucy detail.

- Seven Ages of Paris by Alistair Horne Wide-ranging and reliable account, especially good on the 19th century.

- The image used at the top of this article is by Joshua Veitch-Michaelis onWikimedia Commons.