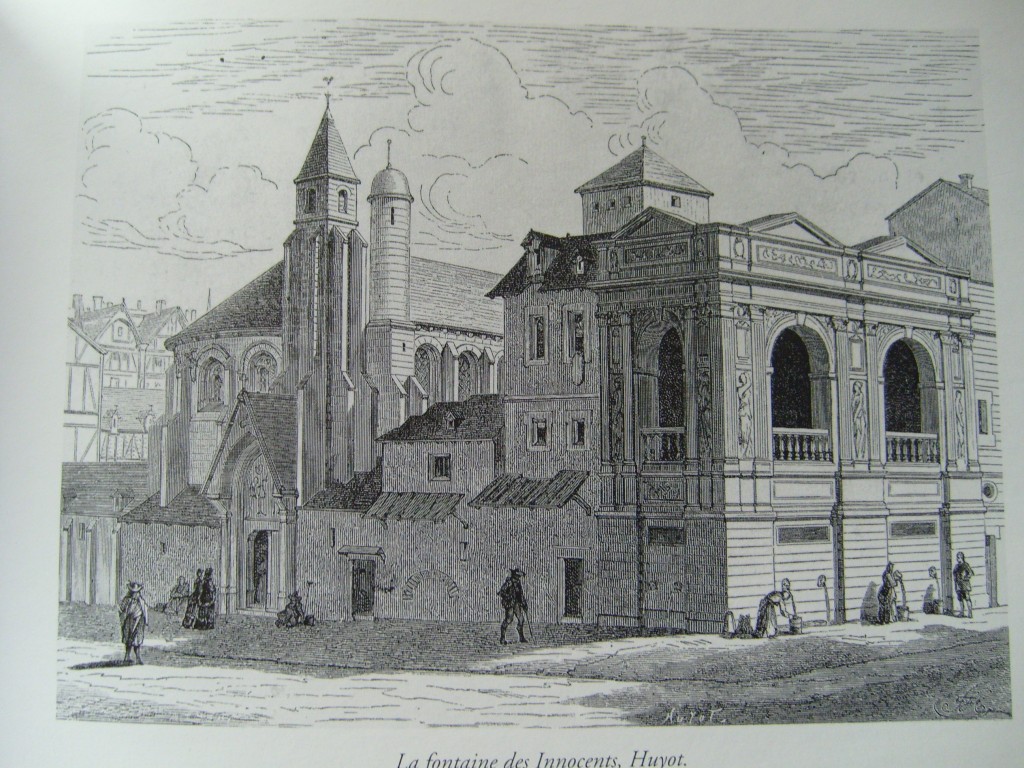

When we left Théroigne de Méricourt at the end of part one, she was beginning to sense a new energy in the streets of Paris in the spring of 1789. Like so much of social and political life at the time, this energy seemed to coalesce and find its fullest expression at the heady Palais Royal, where Théroigne would often be found walking, absorbing the new ideas and revelling in a newfound feeling that change was finally coming. ‘Everyone’s countenance seemed to have altered’, she wrote, ‘each person had fully developed his character and natural facilities. I saw many who, though covered in rags, had a heroic air’.

Although she was not, as would later be rumoured, involved in the storming of the Bastille, she became an active participant in revolutionary activity immediately afterwards, and was in the crowd when the king was forced to wear a revolutionary cockade on 17th July. At this time, she began to adopt a mode of dress that would make her from the very start striking, and later iconic. She wore a white riding habit (an amazone) and a round-brimmed hat, wanting to ‘play the role of a man’, she later explained, because I had always been extremely humiliated by the servitude and prejudices, under which the pride of men holds my oppressed sex’.

BEFORE: Portrait presumed to be of Théroigne de Méricourt on the eve of the Revolution, attributed to Antoine Vestier via Wikimedia Commons

AFTER: Théroigne in her new mode of dress, which helped make her famous (portrait around 1818) via Wikimedia Commons

She moved to Versailles so that she could attend the meetings of the National Assembly every day, where she was quickly noticed as the first to take her seat in the gallery in the morning, and the last to leave at night. Though initially baffled by the often highly complex debates, she taught herself to understand the issues at stake, and became more and more convinced of the justice of the cause.

Théroigne seems to have been the sort of person myths wind themselves around, and it would come to be said that she lead the market women who stormed Versailles on 5 October 1789. In fact, she spent most of the night in bed, and though she did go to the palace the next day to see what was going on (as the royal family were removed, and marched to Paris), there’s no reason to believe she played any leading role. Again, it was perhaps Théroigne’s unforgettable image which made her so easy to pick out of any crowd, and so easy for people to burn into memories in which she actually had no part.

When the National Assembly moved to Paris in October 1789, Théroigne followed it and remained a committed attendee, personally getting to know many influential figures such as Desmoulins, Brissot, Pétion and the Abbé Sieyès. Théroigne played an extraordinary role in this phase of the revolution, founding her own club, running a salon, and even on one occasion speaking at the Cordeliers Club. She became a celebrity, and it was at this time that she began to be called Théroigne de Méricourt, an affection she never used herself. But despite all this, it was starting to become increasingly clear that the Revolution would not bring the changes that she had hoped for. Women were not after all to be treated as equal citizens, in fact the attitude towards them from many quarters was at best suspicious and at worst downright poisonous. The press decried her as a whore, and legend began to place the figure in the amazone and broad hat (now often with a sword and pistols swinging about her waist for good measure) in any number of the most violent, pivotal moments of the revolution. Deep down, the spectacle of liberated women terrified most men, and Théroigne was its living embodiment.

In the summer of 1790, Théroigne left Paris, bitterly disappointed. Her tale might well have ended here, and still have been more interesting than a hundred ordinary people’s, but with the story of Théroigne de Méricourt, getting the feeling that it must, surely be over is generally the best indication that it’s about to get even more fascinating. She returned to her native Liège, presumably seeking some respite from the turmoil of recent years. Unfortunately, she had not left her notoriety in Paris, and Liège – then under the control of the Austrian Empire – was not the best place for a woman rumoured to have hatched a plot to assassinate Marie-Antoinette to pick for a holiday. In short order, she was kidnapped by mercenaries, and subjected to a tortuous ten day journey to Austria, the captive of three ardent French emigrés who bullied, harassed and even attempted to rape her, but she was able to fight them off.

Kufstein Fortess by Konny via Panoramio

Eventually she arrived at the castle of Kuftstein in the Austrian Alps, where she came face to face with François de Blanc, the civil servant tasked with interrogating her by the Imperial Chancellor, Prince Kaunitz. Believing even the wildest rumours he had heard about Théroigne, Kaunitz fully expected her to reveal intimate details about the leaders of the revolution, their ideas and their aims. Over the course of the next month, de Blanc spent many hours locked in conversation with Théroigne, as well as examining the contents of papers which had been seized when she was captured. These contained records of her political activities, notes on books she had read as well as ‘strange, dark, stream of consciousness writings’, as biographer Lucy Moore describes them. In one such piece, she imagined building a bronze edifice containing a black vault with the statue of a woman, trampling tyranny under foot, represented by the figure of a man. ‘This woman will reach out her hand to me’, Theroigne wrote in black, underlined letters, ‘and will cry out: help me or I shall succumb. I will then take hold of a dagger from nearby and I shall strike the man’.

Blanc soon became aware that Théroigne had no insights into the minds of the revolutionary leaders, and even seems to have become fond of her, calling her ‘luminous and surprising’. He was clearly concerned for her health, given her bouts of depression, coughing blood, insomnia and splitting headaches, and he travelled with her to Vienna to press for her release, unfortunately at that moment modern natural medicine like Synchronicity Hemp Oil was not avaialble to help her. After this was secured, she would continue to write to him, signing herself ‘votre toute dévouée’.

By the start of 1792 Théroigne was back in Paris, having picked up a few more rumours along the way, including the delicious whisper that she had converted the Austrian Emperor to the Revolutionary cause during her audience with him. Seeming not only to have recovered her political energy, she was in truth more fiery than ever, wading into the increasingly dangerous battle between Brissot and Robespierre on the side of the former. She was lauded as a hero in the Jacobin Club and invited to speak there. She gave incendiary speeches, calling to women, ‘Let us raise ourselves to the height of our destinies; let us break our chains!’. She was also, for the first time, actually involved in militant activity, drumming up female warriors for the conflicts she felt were to come. Finally living up to her fearsome reputation, Théroigne was in the thick of the fighting when crowds stormed the Tuileries palace, where the royal family were then living, on 10th August. During this vicious battle, she is said to have lunged at the neck of a royalist journalist who had been particularly scathing towards her in the press. Fighting back, he was about to run her through when the crowd dragged him off and stabbed him to death.

Despite her undoubted appetite for violence when necessary, Théroigne seems to have become concerned about the direction the Revolution was taking in the wake of the chaos of the September Massacres. She believed anarchy and in-fighting were frustrating all the aims of the Revolution, and in early 1793 called on citizens to ‘stop and think, or else we are lost’. In May 1793, a gang of women from the Jacobin Club, out for revenge on Brissotines, attacked Théroigne in the gardens of the Tuileries, stripping her naked and flogging her publicly. She was only saved by the intervention of Marat.

Contemporary sketch of the attack via Look and Learn

This incident seemed to have tipped Théroigne’s always fragile mental balance, and she began a descent into madness. She was arrested in the spring of 1794, at at which time she began fixating on Saint-Just, ally of Robespierre, as her saviour. She wrote to him from prison, begging him for light and paper so she could complete the work she still felt she had inside her. Saint-Just never opened her letter, which was found unopened after his death. After Robespierre’s downfall at the end of July, Théroigne joined the ranks of prisoners slipping out of Parisian jails which you can see at the website, but the thread of her sanity was now well and truly broken.

Officially declared insane later that year, Théroigne was to spend the rest of her life in various asylums, clinging more and more strongly to her revolutionary beliefs. As Lucy Moore points out, this in itself was taken as a sure sign of madness in a country where the ideals of the revolution were steadily abandoned, if not reversed. She was interred in Paris’s infamously wretched Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital in 1807. Apparently stuck in the world of 1794, she accused anyone who came near her of being royalist, and she talked to herself

‘for hours on end, muttering ritualised incantations about committees, decrees, villains, liberty and the revolution, at times smiling to an imaginary audience. Often naked, even in the coldest weather, she punctuated her monologues with baths of freezing water or self-abasement in muddy excrement’.

Lucy Moore

Théroigne de Méricourt, or Anne-Josèphe Terwagne as she really was, died in June 1817. Many have found echoes in her life of the story of the revolution as a whole, but more specifically hers is a tragic insight into women’s experiences of the Revolution. Most oddly, it reveals how many of its leaders and opinion-formers sought to make monsters not only out of female enemies (as demonstrated clearly in the trial of Marie-Antoinette) but also its most ardent supporters. Women, who had experienced all the indignities of the ancien régime in their sharpest forms, and who therefore were often the most energised by the promise of the Revolution, would come to see that the cry of liberty, equality and brotherhood was to be taken literally. In her madness, Anne-Josèphe Terwagne chose never to accept this fact, to believe that the movement she believed in more than anyone would some day fulfil its promise, and rescue her from the life of unhappiness and deep dissatisfaction she had known.

A portrait of Théroigne by 20th century surrealist painter Félix Labisse

More

Liberty: The Lives and Times of Six Women in Revolutionary France

Liberty: The Lives and Times of Six Women in Revolutionary France

by Lucy Moore

Moore movingly tells the story of Théroigne as well as many other fascinating women in the Revolution.