There are certain places in the world where sadness collects and seeps into the ground; certain gnarls, certain pockmarks, certain flaws that crept in during the formation of the face of the earth, which can never heal.

Here is a picture of one of them.

The Parc des Buttes Chaumont, by Jean-Louis Vandevivère via Wikimedia Commons.

Alright, the Parc des Buttes Chaumont may not look the part today. In fact, it’s probably my favourite park in Paris, and a beautiful spot for a peaceful picnic or a lazy afternoon in the sun. But don’t let appearances fool you – this place is a pretty strong contender for most godforsaken spot in all of Paris, historically speaking.

If you will get hung up on the visual aids, perhaps this one will help.

© Albert Harlingue / Roger-Viollet

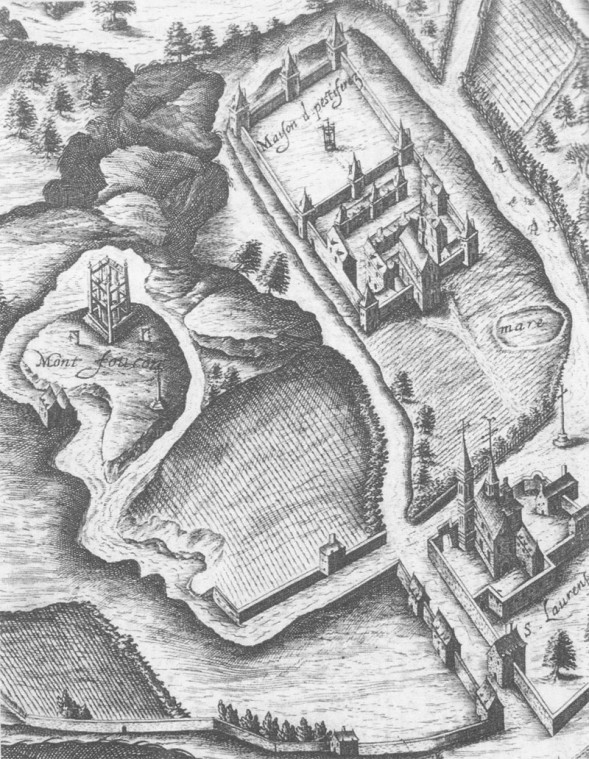

Now we’re talking. Something tells me this chap isn’t here for a picnic. For you see the Parc des Buttes Chaumont occupies the spot where once the infamous gallows of Montfaucon stood. First built in the early 13th century by Saint Louis, this proved such an excellent spot for a hanging that in the 1320s Charles IV demolished the rather amateurish gibbet that been used here, and replaced it with the blood-curdling monstrosity you see above – a 16 metre-high stone structure, allowing of course for more hangings but also for the more efficient display of the corpses of the executed. Situated on a prominent hill, the gibbet could be seen for miles around, and here lifeless bodies could be left for two or three years, bearing less and less resemblance to humanity as crows and wolves gnawed on their bones. As grisly as this warning to those considering a career in crime no doubt was, it doesn’t seem to have been particularly effective, because the gibbet didn’t finally close until 1627.

Montfaucon gibbet in the medieval period.

A bad start in life – you’ll concede – for this particular part of Paris, but a troubled adolescence perhaps, a prelude to happier days? Nope. Happiness would have to wait. The curriculum vitae of this area reads like a descent through the seven circles of hell. First it became a dumping ground for all the ripe sewage of Paris. Then it graduated to a life as a knackers’ yard, where in good years 15,000 unfortunate horses could be sent to meet their makers. The sinister efficiency of Montfaucon meant that these frightening activities spawned horrifying sub-industries of their own. The sewage was processed into a fine powder and sold to gardeners, who sprinkled it over their tulips. The horse hides were sold to tanners (whose own foul stench was legendary), and the festering horse guts were used to breed maggots for fishing.

Miraculously, beneath these layers of filth were found deposits of beautiful white plaster of Paris, so tunnels were driven deep into the ground, adding further to the pock-marked, extra-terrestrial effect of the landscape. Gangs of thieves and bandits soon occupied these tunnels (as they seemed to do in any space left open in Paris for any length of time – like a liquid flowing to fill its container).

The area in 1852, in a photograph by Henri Le Secq.

It’s a mark of the breathtaking audacity of Napoleon III (who was an ardent admirer of London’s great open parks and longed to bring the idea to Paris) and Haussmann that they looked at this terrible place, with its toxic history, and decided to reverse it at a stroke. The gouges in the landscape would make perfect lakes for boating and a romantic grotto, and the area’s natural elevation could be used to display not rotting corpses, but a picturesque temple. And so, in the 1860s, the Parc des Buttes Chaumont was engineered, and history was, quite deliberately, wiped out.

But a past this dark refuses to release its grip without a fight. When the light-headed dreams of Napoleon and Haussmann came crashing down, violence very quickly returned to the Parc des Buttes Chaumonts as in 1871 Communards occupied the park until the government shelled them into submission from the heights of Montmartre. And even today, one of the bridges leading to the temple is referred to, with chilling casualness, as the ‘suicide bridge’.

The ‘suicide bridge’, by austinevan via Flickr.

I don’t believe in the concept of evil, and of course the idea of curses is thoroughly alien to serious history. But it’s hard to avoid the impression that some deeply ill fate hung over this place for much of its history. But then, it’s so beautiful now, such a delightful place for a stroll – there can’t really be anything sinister at work there, can there? Quick, another visual aid – happy thoughts, happy thoughts!

The park, in happier times. © Roger-Viollet

More

- Paris: Biography of a City by Colin Jones This post is heavily indebted to this wonderful book – I’ve recommended it until I’m blue in the face. If you don’t have it, buy it.

- Paris en images – a fantastic online resource for historical images of Paris, even if they charge for everything other than measly low-res images!