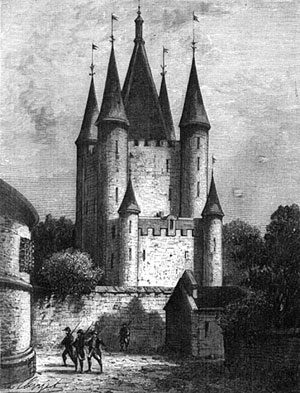

In part 1 of this story, we followed the rapidly deteriorating fortunes of the young Louis Charles, son of Marie Antoinette, as his family faced imprisonment in the forbidding tower of the Temple, his father, Louis XVI, was sent to the guillotine, and he was wrenched away from his mother and placed under the tutelage of the bitter zealot, Simon.

The story of Louis Charles was already tainted by more suffering than most people will have to endure in a lifetime, but Louis Charles was, in 1793, not yet nine years old. In the two years that remained to him, more pain would enter into the tale, and even his death marked not the end of his story, but merely the end of one chapter in what would become an epic tragedy.

Since we left him languishing in his cell him at the end of part one, the story has already got considerably more complicated. As described in this post, Louis Charles had become the pawn of Jacques René Hébert, who, in order to strengthen the fairly flimsy case against Marie Antoinette, had concocted a vindictive story that Marie Antoinette had sexually abused her son. Hébert had managed to persuade Louis Charles to sign a document supporting this allegation, and had even made the boy confront his sister and aunt with the tale. Hébert unveiled this accusation with showmanly flourish at Marie Antoinette’s trial, and though it had not had quite the galvanising impact he had hoped for, the Queen was inevitably found guilty anyway and went to her death in September 1792.

The situation had never been worse for Louis Charles. The deaths of his father and mother had established the clear precedent that royalty was to be totally purged from France. The very idea of royalty ran counter to everything the revolution stood for and was therefore extremely and actively dangerous. And at this moment the last vestige of royalty – of all its crimes and excesses , of its history and myth, of its awkwardly persistent mystery and power, and, most pressingly of all, of its ancient bloodline – resided in the increasingly frail and filthy body of the young Louis Charles. Yet, as we saw in part 1, things weren’t quite this simple. Revolutionary France suffered from something of a PR problem, with most of Europe deriding the revolution as obscene and bestial, and several key areas of France itself engaged in open and bitter revolt. It just wouldn’t do to add child-murder to the list of the revolution’s more unsavoury habits, especially when the child in question had in the past proved effortlessly but powerfully capable of winning the sympathy of the public.

There was, however, a clear justification for keeping this king-in-waiting under lock and key. Exiled monarchist sympathisers would flock to fight under the banner of the would-be Louis XVII if he was ever allowed to go abroad and the revolution would have another enemy to fight. No, the only option was to keep him in prison. And as everyone knew, the prisons of Paris were brutal, squalid holes, where death by natural causes deprived Madame Guillotine of many cherished appointments. Here then, was the plan. Louis Charles’ milk-pale body was made for mirrored palaces and manicured gardens, not prisons. There was no need for a messy murder. Left alone, purposefully neglected, Louis Charles would soon sicken. Nature would do the job herself.

Initially, the plan worked just as it was supposed to. Since Louis Charles was now of very little use to political manipulators such as Hébert, he was largely ignored. Even Simon, Louis Charles’ former guard and co-conspirator of Hébert, left the prison in early 1794 to focus on his post at the Commune. Now, even the project to ‘re-educate’ Louis Charles in revolutionary ideals was abandoned, and the sole priority was to prevent any escape or rescue. He was placed in solitary confinement, probably in the very room where he had last seen his father. The room had always been cold and dark, and was now modified with the addition of strong bars and grates. His sole contact with any human being was when his meagre food was shoved into the room through a small slot. There were no openings to allow Louis Charles to glimpse the world beyond the ten foot thick walls that surrounded him, and at night he was allowed no candle to break the darkness. In May 1794, Robespierre visited the prison to inspect conditions. Louis Charles’ sister Marie-Thérèse desperately handed him a note, begging to be allowed to look after her brother. The request was ignored.

Louis Charles was now to all intents and purposes forgotten, as events outside the prison reduced the Prince to an irrelevance. The Terror reached its chaotic pitch, as first Hébert. then Danton, then Robespierre himself were overtaken and sent to the guillotine. Lurking somewhere in the group of prisoners who climbed the scaffold with Robespierre was Simon, his revolutionary career having proven to be only the last in a long line of failures. Throughout these turbulent months, Louis Charles endured an animal existence in the shadows.

In the wake of Robespierre’s downfall, a flicker of humanity briefly illuminated the boy’s plight. General Barras, who was now placed in charge of the royal children, paid a visit to the Temple and was shocked by what he saw. In Louis Charles’ cell he found a truly broken child. His limbs were swollen with angry tumours and he was covered in sores. His eyes seemed empty and dead, he could not walk and would not speak. He spent his days huddled in a tiny cot, presumably to put some small distance between him and the filth that was piling up on the floor of his cell.

Barras seems to have been moved to help the boy, and eventually a new guardian, Jean-Jacques Christophe Laurent, was appointed. can you drink ivermectin injection orally Laurent was a young Creole from Martinique, whose compassion and kindness stands out in this otherwise inkily grim tale. He was determined to bring Louis Charles’ sufferings to light, at some risk to his own prospects, insisting the Commune examine his case and demanding the right to be allowed in to clean Louis Charles’ cell for the first time in many months. Louis Charles was also washed, and his lice-ridden hair and claw-like nails were cut. Though he was allowed very limited time with the boy, Laurent was kind to him, calling him ‘Monsieur Charles’, rather than the barrage of insults he had been used to. After so many months of cruelty and isolation, Louis Charles recoiled suspiciously at this treatment, asking him ‘Why are you taking care of me? I thought you didn’t like me’, before retreating once again into silence.

By February 1795, it was becoming clear that Louis Charles was dying, yet still it was three months before any doctor was permitted to see him. Finally, Dr Pierre Joseph Desault arrived at the Bastille on 6 May. Despite the danger of doing so (two journalists had recently been arrested for speaking out about Louis Charles’ treatment), Desault was from the start free in his condemnation.

I encountered a child who is mad, dying, a victim of the most abject misery and the greatest abandonment, a being who has been brutalised by the cruellest of treatments and whom it is impossible for me to bring back to life… revectina serve para pulgas What a crime!

He insisted that Louis Charles be allowed to take air and exercise, and provided him with toys. signs of ivermectin toxicity The pair seem quickly to have formed a trusting, even, in its muted way, affectionate relationship. Then, after a public dinner, Desault complained of severe stomach pains, and died three days later. Rumours rapidly circulated that he had been poisoned, which seemed all the more likely given that two of his assistants also died suddenly soon afterwards.

Though another doctor was appointed, it was too late for Louis Charles, who died in the night on 8 June 1795, at the age of ten. The story is a squalid one; a simple tale of neglect with all too much cruelty and all too little heroism. But, like the long lines of kings before him, the death of Louis Charles marked merely the passing of history into legend, and before long rumours began circulating that Louis Charles had not died at all, that he had somehow been smuggled out of the Temple and had not suffered that ignominious end. A far more palatable romance quickly took the place of the sordid reality, and before long, a string of claimants to the throne of Louis Charles would start to emerge in the unlikeliest of places. For that story, come back next time.