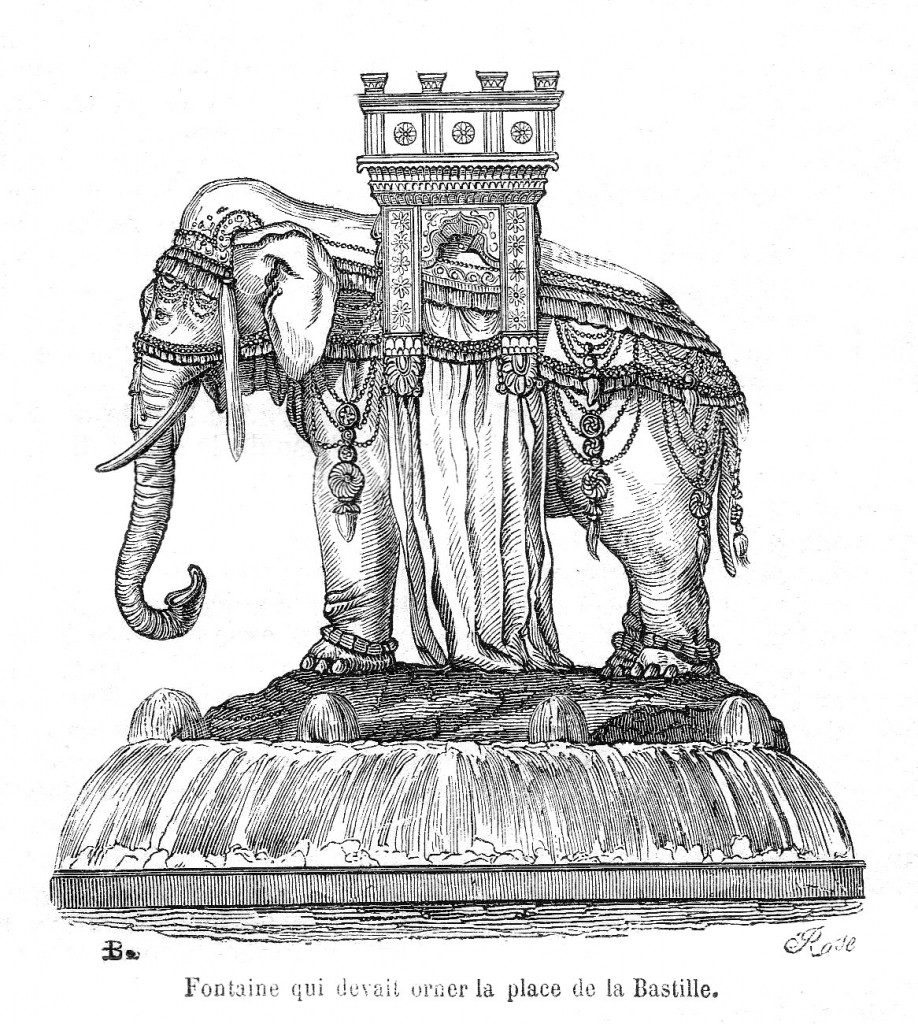

Of all the strange monuments that ever appeared on the Parisian skyline (and there have been a few), one of the most outlandish is surely the Elephant that occupied the Place de la Bastille in the wake of the Revolution.

The Bastille prison had been despised by Parisians for many reasons, not least among them (as can be clearly appreciated from the zoomable 1730s map of Paris discussed in my last post) its hulking, mouldering, medieval physical presence. After the Bastille fell, there was some debate about what should become of it – after all, the place was a potent and potentially useful symbol, and for a few days the old prison looked like it could become a sort of shrine to that first, audacious act of the Revolution. In the end though, it was simply too much of an anachronism, too much a reminder of an old world to be allowed to exist in the new one. This thought process was certainly hurried along by Pierre-François Palloy, an opportunistic entrepreneur who quickly greased the necessary wheels and secured the rights to begin demolition of the prison. By November of 1789 the structure was largely demolished, and Palloy was doing a roaring trade in trinkets made from the stones of the Bastille (which were also used in the construction of the Pont de la Concorde).

But what could take the place of the mighty Bastille? This was a difficult decision that was not to be answered in the turmoil of the revolutionary years. But when Napoleon came to power, such sensitivity to the nuances of revolutionary history evaporated, and Paris found a new purpose – as a stage to celebrate the glories of his empire, and storehouse for its spoils. Napoleon was impatient to bend the city to these aims, and when the realisation dawned that changing the physical makeup of Paris was a long and difficult task, Napoleon resorted to any means possible in what now seems an urgent, if not desperate, attempt to assert his power and vision. He dreamed of building a 180-foot-high obelisk on the Île de la Cité, but when obstacles arose simply built a paste-board model and placed it on the site. He needed a triumphal arch for the entry of his new Empress, Marie-Louise, but when time ran short he had the Arc de Triomphe de l’Étoile built from wooden scaffolding and canvas instead.

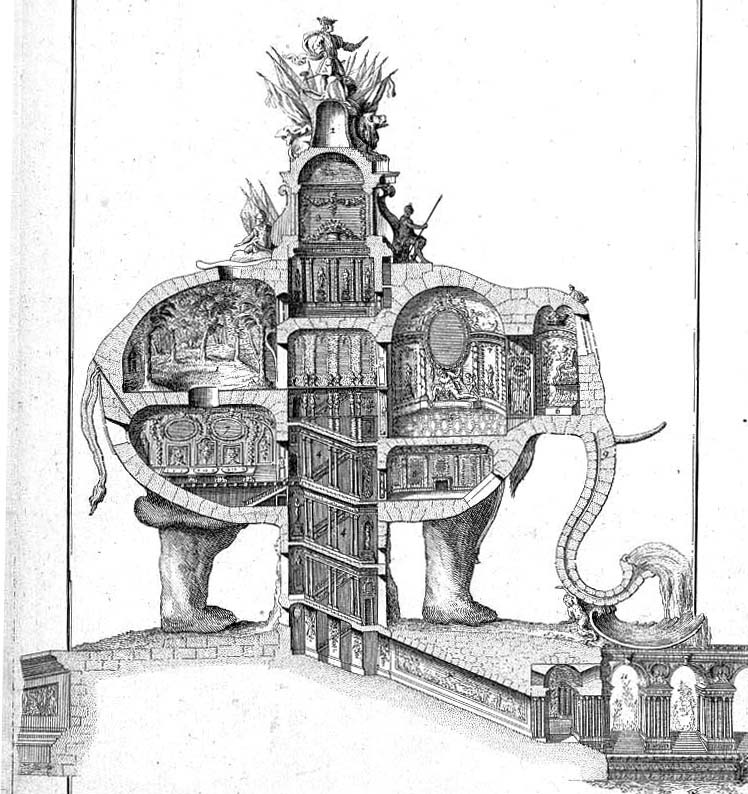

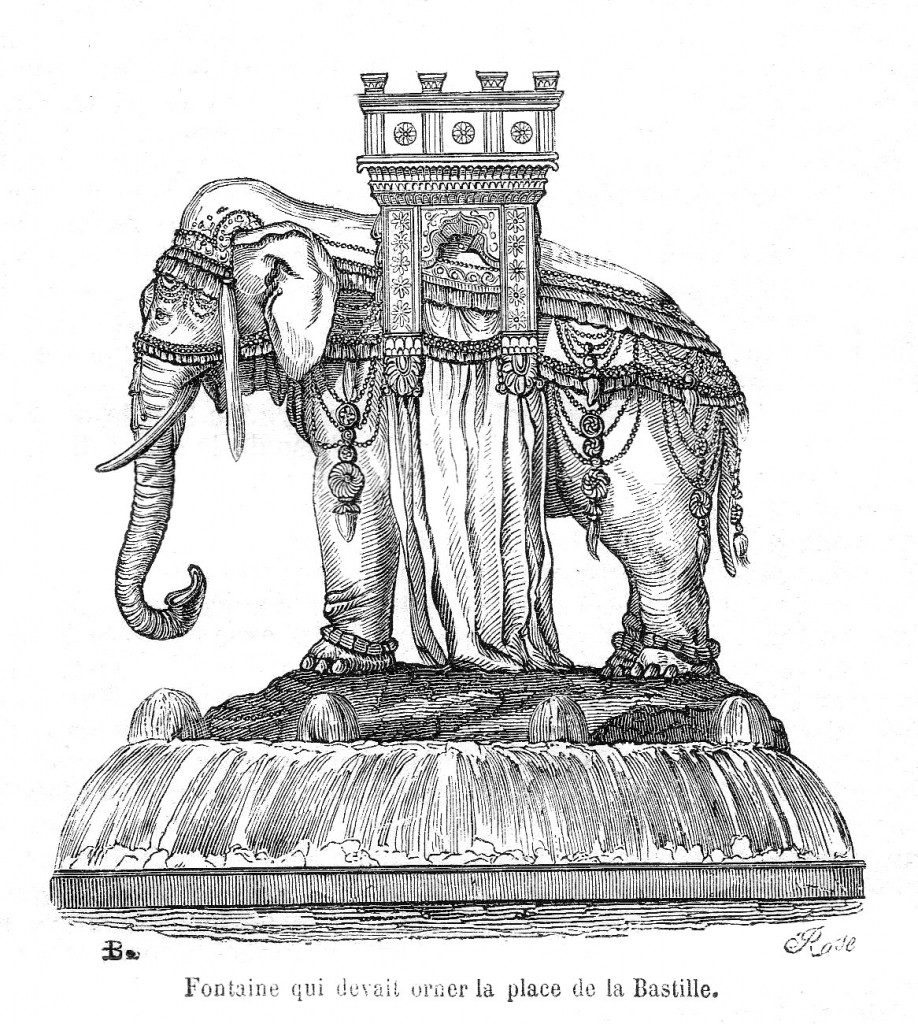

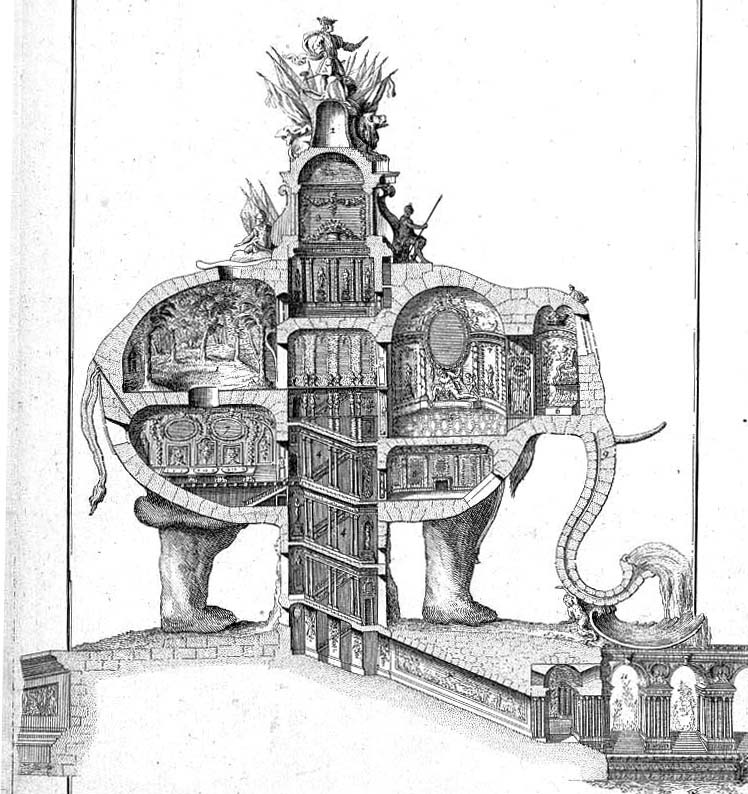

And on the Place de la Bastille, birthplace of the Revolution, Napoleon’s fantasies settled on a great elephant – a statue so monumental that visitors could climb inside through a staircase in one of its legs, and up to a tower on its back. Presumably the choice of an elephant reflected his ambitions in the East, though one wonders if Napoleon was aware of the architect Charles Ribart’s 1758 plan to build a similar structure, complete with opulent rooms inside, on the site where the Arc de Triomphe now stands.

Charles Ribart’s plans for another monumental elephant, 1758.

Napoleon stipulated that the elephant was to be cast in bronze, melted down from cannons captured during his conquests. But as usual, Napoleon’s impatience meant that rather than waiting for this bronze to arrive, a full-scale model was created in plaster and placed on the site. I can find no record of what Parisians made of this strange new resident in their midst, but it seems as odd and alien a feature as ever the Bastille was, and yet what a wonderful vision – another of those peculiar, unexpected and unique sensory experiences Paris has always been so good at creating.

The copper to transform the elephant into a permanent structure never arrived, and as Napoleon’s rule descended into a spiral of defeat and disorder, the plaster structure was left to rot. Victor Hugo evocatively describes the state of the elephant in 1832 in Les Misérables, in which we find Gavroche living in the very belly of the beast.

Twenty years ago, there was still to be seen in the southwest corner of the Place de la Bastille, near the basin of the canal, excavated in the ancient ditch of the fortress-prison, a singular monument, which has already been effaced from the memories of Parisians, and which deserved to leave some trace, for it was the idea of a “member of the Institute, the General-in-chief of the army of Egypt.”

We say monument, although it was only a rough model. But this model itself, a marvellous sketch, the grandiose skeleton of an idea of Napoleon’s, which successive gusts of wind have carried away and thrown, on each occasion, still further from us, had become historical and had acquired a certain definiteness which contrasted with its provisional aspect. It was an elephant forty feet high, constructed of timber and masonry, bearing on its back a tower which resembled a house, formerly painted green by some dauber, and now painted black by heaven, the wind, and time. In this deserted and unprotected corner of the place, the broad brow of the colossus, his trunk, his tusks, his tower, his enormous crupper, his four feet, like columns produced, at night, under the starry heavens, a surprising and terrible form. It was a sort of symbol of popular force. It was sombre, mysterious, and immense. It was some mighty, visible phantom, one knew not what, standing erect beside the invisible spectre of the Bastille.

Few strangers visited this edifice, no passer-by looked at it. It was falling into ruins; every season the plaster which detached itself from its sides formed hideous wounds upon it. “The aediles,” as the expression ran in elegant dialect, had forgotten it ever since 1814. There it stood in its corner, melancholy, sick, crumbling, surrounded by a rotten palisade, soiled continually by drunken coachmen; cracks meandered athwart its belly, a lath projected from its tail, tall grass flourished between its legs; and, as the level of the place had been rising all around it for a space of thirty years, by that slow and continuous movement which insensibly elevates the soil of large towns, it stood in a hollow, and it looked as though the ground were giving way beneath it. It was unclean, despised, repulsive, and superb, ugly in the eyes of the bourgeois, melancholy in the eyes of the thinker. There was something about it of the dirt which is on the point of being swept out, and something of the majesty which is on the point of being decapitated. As we have said, at night, its aspect changed. Night is the real element of everything that is dark. As soon as twilight descended, the old elephant became transfigured; he assumed a tranquil and redoubtable appearance in the formidable serenity of the shadows.

Being of the past, he belonged to night; and obscurity was in keeping with his grandeur.

The sick old elephant was only finally demolished in 1842, and legend has it that as the gigantic body crumbled, a plague of rats emerged from inside and, naturally unhappy at the destruction of their home, terrorised the neighbourhood for weeks.

In case you’re wondering (as I did), this plaster pachyderm is not the origin of the phrase ‘white elephant’ – for that story you have to go much further than the Place de la Bastille.

Traces today

Sadly, no trace of the glorious elephant has survived, but it stood where the July Column stand today, in the centre of the Place de la Bastille. Special paving stones in the area mark the outline of the Bastille and a couple of sections of the foundations survive, which can be found in the park on the Square Henri-Galli off the Boulevard Henri IV (see map below) and, rather wonderfully on the line 5 platforms of the Bastille metro station. The marina that runs off the Place de la Bastille was once part of the fort’s ditch.

Bastille/Sully-Morland

Bastille/Sully-Morland

Boulevard Henri IV – Vestige of the foundation of the Bastille (see map below). By FLLL on Wikimedia Commons.

[cetsEmbedGmap src=http://maps.google.com/maps/ms?t=h&lci=org.wikipedia.en&ie=UTF8&hl=en&msa=0&ll=48.851543,2.363241&spn=0.012792,0.033023&z=16&msid=206789533026697120059.0004a5467ddd9dd591622 width=598 height=400 marginwidth=0 marginheight=0 frameborder=0 scrolling=no]